In a report on the 2018 National Latin Exam Survey, the number of teachers primarily using grammar-translation (478) was over twice that of the next most-used “Reading Method” option (202), and over 16 times that of the least-used “Active Latin” option (27). The other options given were CI, and TPRS. You might already see the problem there. That is all those options were labeled as “methodologies/techniques/philosophies” on the survey, likely in an attempt to account for all the differences between terms. However, such a comparison is like asking “what do you primarily do in class?” That is, there’s almost no coherency between the five options. For example, a teacher could use the TPRS method to provide CI, and in doing so be characterized as using Active Latin. The only clearly distinct option is grammar-translation, yet that still doesn’t show the extent to which grammar is present in one’s teaching (i.e. grammar is also included in “Reading Method” and possibly “Active Latin”). Therefore, I wanted to send out a new survey that focused on practices rather than terms prone to misunderstanding. I did just that in June of 2020. In this post, I share those results…

Continue readingCurriculum

CI, Equity, User-Error & Inequitable Practices

I don’t agree that the statement “CI is equitable” is harmful. Yet, I also don’t think the message behind “CI isn’t inherently equitable” is wrong, either. John Bracey said one can still “do racist stuff” while teaching with CI principles. Of course, we both know that’s an issue with content, not CI. Still, I get the idea behind that word “inherent.” In case you missed the Twitter hub bub, let me fill you in: People disagree with a claim that CI is “inherently equitable,” worried that such a message would lead teachers to say “well, I’m providing CI, so I guess I’m done.” I don’t think anyone’s actually saying that, but still, I understand that position to take.

Specifically, the word “inherent” seems to be the main issue. I can see how that could be seen as taking responsibility away from the teacher who should be actively balancing inequity and dismantling systemic racism. However, teachers haven’t been as disengaged from that equity work as the worry suggests. I’ve been hearing “CI levels the playing field” many times over the years from teachers reporting positive changes to their program’s demographics. What else could that mean if not equity? But OK, I get it. If “inherent” is the issue, maybe “CI is more-equitable” will do. If so, though, at what point does a teacher go from having a “more-equitable” classroom to an “equitable” one? And is there ever a “fully-equitable” classroom? I’m thinking no. So, if CI is central to equity—because you cannot do the work of bringing equity into the classroom if students aren’t understanding (i.e. step zero), and nothing has shown to be more equitable than CI, well then…

For fun, though, I’ll throw in a third perspective. Whereas you have “CI is equitable” and “nothing makes CI equitable per se,” how about “CI is the only equitable factor?” I’m sure that sounds nuts, but here it goes: Since CI is independent from all the content, methods, strategies, etc. that teachers choose, as a necessary ingredient for language acquisition, CI might be the only non-biased factor in the classroom. Trippy.

I don’t think that third perspective is really worth pursuing, though, so let’s get back to the main points. Again, I understand the message behind “CI isn’t inherently equitable” as a response to “CI is equitable.” However, I suspect the latter is said by a lot of people who aren’t actually referring to CI. Don’t get me wrong; some get it, and are definitely referring to how CI principles reshaped their language program to mirror demographics of the school. However, others are merely referring to practices they think is “CI teaching.” This will be addressed later with the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Otherwise, let’s talk equity…

Continue readingBackward Design: Bad For Languages

TLDR; Don’t use UbD, especially this next year. COVID-19 messed with everything, so keeping the same expectations is unreasonable. Let’s face it…there’s not going to be any miraculous “catch up,” nor should we expect that. Instead of guessing where students will be in the fall, and how far their proficiency might develop with all the disruptions, try Forward Procedure.

I began writing this post after seeing calls from a lot of language teachers seeking tech tools as answers…to all the wrong questions. Rather than trying to maintain what we’ve done, we’re gonna need to make considerable adjustments to our expectations. Curricular design is one of those.

Backward Design

Sure, it makes perfect sense. You start with the result you want for your students, then go backwards from there, planning learning experiences along the way. It’s been recognized as good teaching across all content areas for at least a decade, and has been around since the late 90s. This is “textbook” best practice. In fact, it’s literally a textbook…

1969: 50 Years of “4%ers”

Just a few months after the moon landing, Superintendent John Lawson (Shaker Heights, OH) gave a speech at the Symposium on Foreign Language Teaching at Indiana University. Its age certainly shows. Then again, were it not for the typeface, you’d think some of these statements appeared yesterday in a blog! I find it striking that such “progressive” and “controversial” ideas have been discussed for 50 years, pretty much coinciding with the civil rights movement, yet without much fundamental change to either. There’s no excuse for the latter. As for second language teaching, that’s slightly more understandable considering the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) was hardly established by the late 60s.

To give you a sense of how relevant Lawson’s ideas are today, look at this statement addressing the importance of compelling topics, and what now has become criticism against using unadapted texts driving the AP Latin problem:

There’s also a section, while brief, managing to address topics like teaching to the test, teacher perception of status in their field, elitism, exclusivity, ineffective pedagogy, compellingness, connectedness, comprehensibility, and confidence. All that back in 1969. Holy moly, right?!

That speech also happens to be the source of the “4%er” term that Keith Toda just shared in his latest (and last-for-a-while) blog post. Now, Keith is somewhat of a self-proclaimed man of the shadows not really active on social media, so my first thought was that he didn’t know the “4%er” term doesn’t really come up these days. In fact, I had to go back to a 2015 moreTPRS list email to search for the references contained in here! But maybe that term is exactly what teachers need to be reminded of right now. Let’s start with its history:

Continue readingPisoverse eBooks Are Here!

**Updated 8.1.20 with this All-Access Pisoverse & Olimpi combo**

The world feels like it’s burning right now. Everyone should pay close attention to police brutality, those defending it, and so-called “leaders“ encouraging it and inciting further violence from white nationalists. If we can’t stand against systematic racism directly, we must be observant of what’s going on in solidarity. No one gets to tune this out, and if you do, recognize that privilege. So, this eBook announcement of mine is insignificant in comparison. Nonetheless, teachers’ attention at some point will have to shift to next year’s micro world of school and the classroom. This is what I have to offer when it comes to putting out some of those fires.

I’ve teamed up with Storylabs to offer the Pisoverse in digital form. All novellas are now available as an annual subscription for ALL your students (up to 180…and if you have more than 180, may the Olympian gods hep you!). Options include single books, packs of 3, or complete Pisoverse All Access. The eBooks are all web-based, and a school-safe certificate is on its way for a downloadable app.

Storylabs also has some tools for teachers, like tracking how long students spend reading, built-in notebooks, and the ability to create, share, and use resources other teachers have made for each book! If you have ideas, there’s a link to a Google form in each book’s Index Verbōrum. Or, fill that out directly, now. Unlike some textbook companies, we want to encourage collaboration between teachers sharing materials that support reading novellas. Just be sure to check first to see if you’re creating something that already exists in a Teacher’s Guide! Oh, and all the narration and Audiobooks I’ve recorded is included with the eBooks on Storylabs! Each student can listen to every chapter as many times as they want while reading at their own pace. There’s also built-in adorable Italian pronunciation for the few books I haven’t recorded, too!

Continue readingtrēs amīcī et mōnstrum saevum: Published! (Oh, And eBooks Are Coming…)

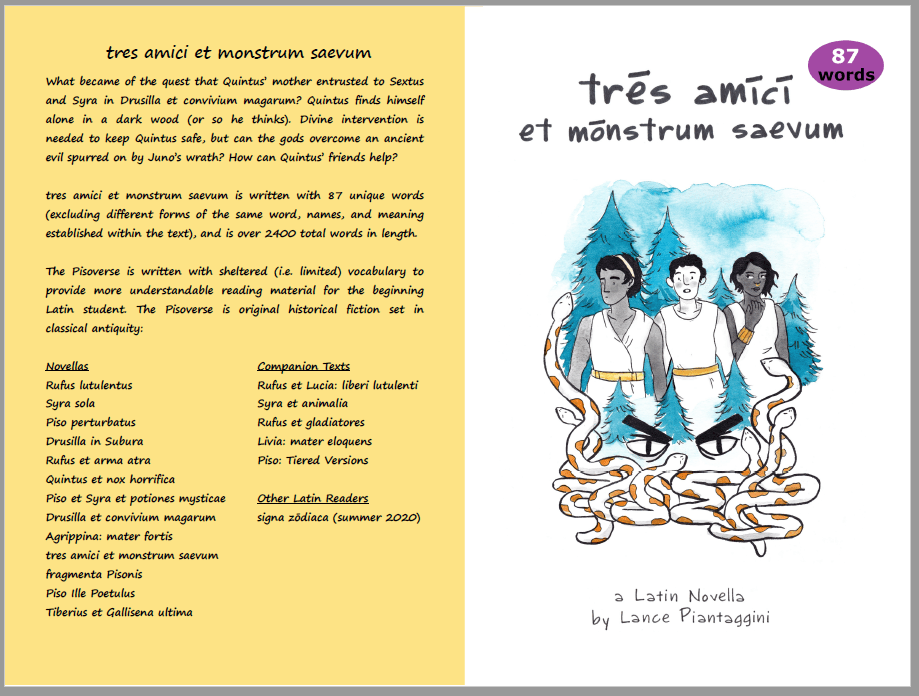

Quintus, Syra, and Sextus are back together again in this tale of 87 unique words (excluding names, different forms of words, and meaning established in the text), nearly a third of which are super clear cognates, with a total length of over 2,400 words.

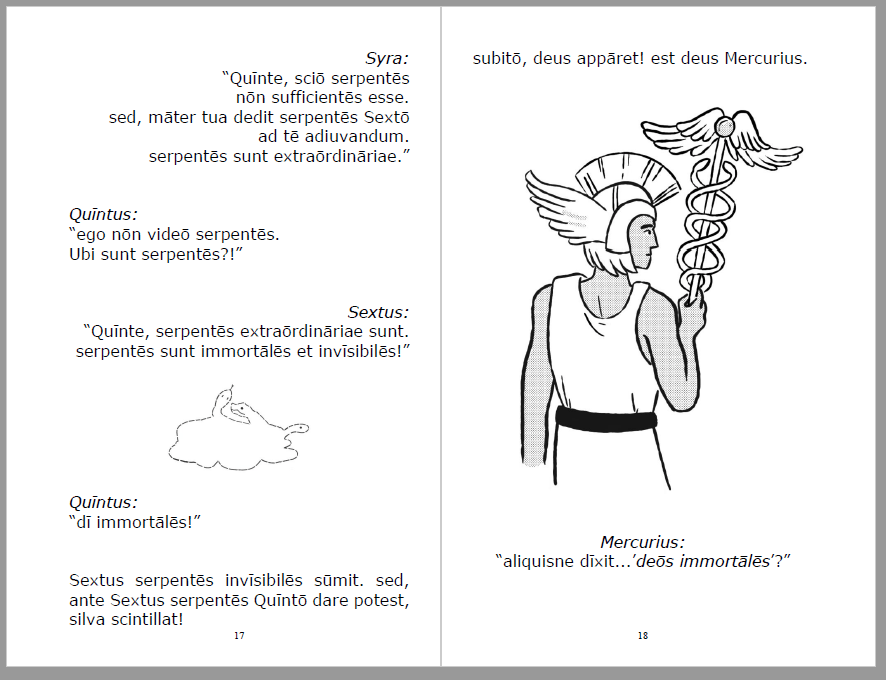

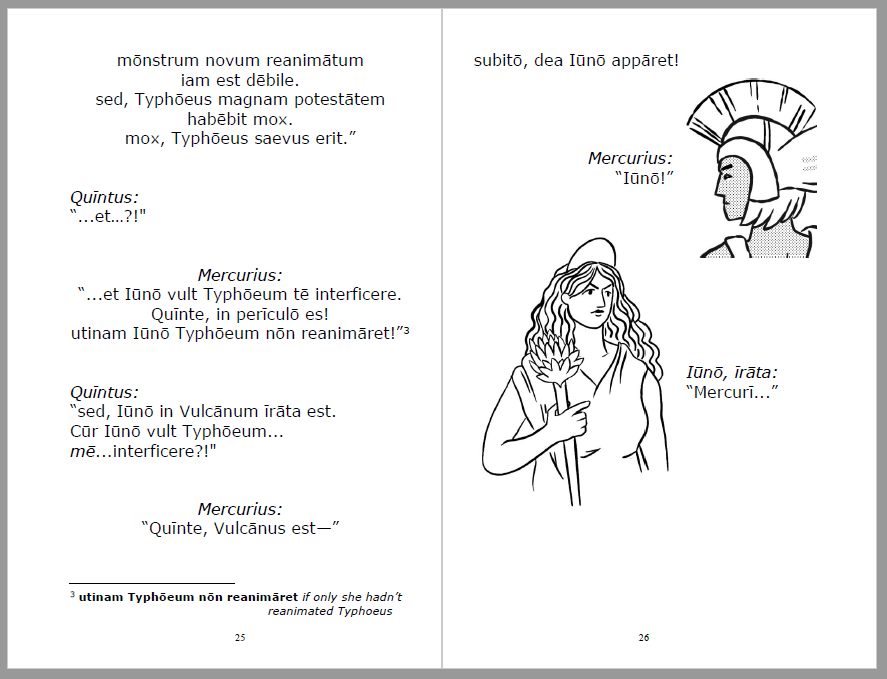

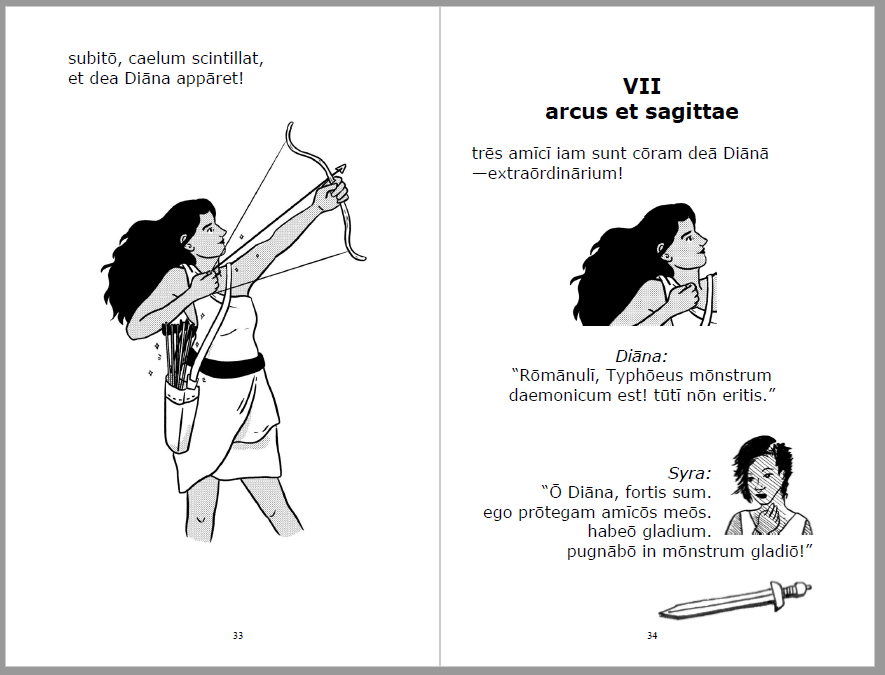

What became of the quest that Quintus’ mother entrusted to Sextus and Syra in Drūsilla et convīvium magārum? Quintus finds himself alone in a dark wood (or so he thinks). Divine intervention is needed to keep Quintus safe, but can the gods overcome an ancient evil spurred on by Juno’s wrath? How can Quintus’ friends help?

A new Pisoverse illustrator, Chloe Deeley, has updated Quintus and Sextus to show their increased age over time. Chloe has also contributed to the Pisoverse by depicting deities Mercury, Juno, Diana, and Vulcan.

This is my favorite book yet. If you find any typos in the second half of the book, it’s because each time I’ve edited, the narrative keeps me turning pages pretty fast! Oh, right. eBooks are coming for the entire Pisoverse. Stay tuned here. For now, trēs amīcī et mōnstrum saevum is available…

- On Amazon

- Free preview (first 4 of 12 chapters, no illustrations)

- For Sets, Packs, and Bundle Specials, order here.

- To instantly listen to and download the audio, go here.

How To Teach The Infinitive

But first, what’s an example without a non-example, really? When it comes to pedagogy, I’d call that partial information. Maybe you’ll know what to do after learning something, yet maybe it’s not clear what to avoid while also doing that thing. We can’t just stack practices upon practices and expect things to turn out well.

Typical Instruction (i.e. the non-example)

An introduction to the infinitive is usually taught by first focusing on the form “-re” with an incomplete, yet easy-to-test explanation (e.g. “the infinitive means ‘to X'”). Students are shown examples using different verbs (i.e. multiple meanings) in isolation, phrases, and/or short sentences. Then, students practice identifying infinitives, and changing verbs into their infinitive form. That’s basically it. The kids who memorize the “-re” form (while also not confusing it with the other…hundred?…forms that were taught by now) as well as verb meanings (i.e. the kids who have good memorize) are successful. One thing to note here is that the examples and practice sentences tend to lack meaning or purpose within a context. That is, even if there’s some continuity from sentence to sentence, the purpose is still identifying infinitives, not reading to find out what the messages are about. Stop doing all that. Here’s how to teach the infinitive…

What Is A Language Curriculum?

Modern and classical language teachers alike have been using big name textbooks for decades, yet there’s been an emerging counter culture known broadly as “untextbooking.” This movement is a response to a) the lack of proficiency, b) dropping interest/enrollment, and c) the kind of exclusivity that form-based textbook teaching has an affect on. Instead, preference within the “untextbooking” movement is given to meaning-based teaching that results in greater proficiency, higher enrollment, and a removal of obstacles, making language programs more inclusive. For years now, I’ve heard things like “there’s not enough culture,” or “this lacks curriculum support,” or some other complaint suggesting that textbooks have something necessary to offer that not-textbooks don’t. It’s been shown that textbooks can overload learners with too much vocab, grammar rules, and target-culture details (in English). However, I’m more interested in the role of proficiency. That is, for all the supplements textbooks might bring to the curriculum, what do they really do for language proficiency? Where does proficiency come into play in a curriculum?

Language proficiency generally refers to one’s unrehearsed ability to communicate (e.g. listening, reading, seeking clarification, replying, sharing ideas, asking questions, etc.). Humans can’t plan to communicate genuinely (e.g. “ready, communicate!”). It’s just something that happens when there’s a reason to do so. The following curricular questions keep language proficiency in mind (vs. studying about languages, or cultures, or memorizing vocab, which requires little to no proficiency)…

Ginput

No, this does not describe a juniper and coriander-based evening. Ginput is Grammar-based Input. Surprise! Yeah, I played this one pretty close to the vest this year. In fact, I began writing this post on June 13th—2019—knowing it would be months until actually implementing and seeing any results from what was last year’s springtime idea.

What’s Ginput?

The idea for Ginput came shortly after one of those frequent grammar debates online fizzled out. I still know that teaching grammar isn’t necessary, and I certainly won’t test grammar knowledge, but I also know that even really compelling things get boring throughout the year! I started wondering if grammar had a role to play, if only as a break from all the compelling stuff, especially since I had no plans to test or grade it. However, a question remained: “could grammar somehow be input-heavy?“

The Search for Grammar-based Input

Providing CI while teaching grammar is rare, so I began to think…“But what if teaching grammar weren’t the entire syllabus?” and “Could I explore Latin grammar with students knowing that our curriculum is based on their interests (i.e. NOT grammar) under a comprehension-based and communicative language teaching (CCLT) approach?” I was certainly onto something, but needed a resource for guidance. Oh wait, I wrote one…

Quīntus et nox horrifica Audiobook + 7 New Audio Albums

This is pretty spooky.

I teamed up with Michael Sintros (Duinneall) to create an audiobook accompanying Quintus’ scary night home alone, a personal favorite of my novellas. The ambient music makes for quite the cinematic experience when listening (with or without reading). Just like interactive sound effect reading in the classroom, this audiobook helps “play a movie in your mind” of what you’re listening to/reading—a true sign of comprehension. The music and effects could be straight out of a suspense film. In fact, listen to this at home, in the dark. I dare you! I can’t wait to get back to the classroom next year, set up chairs in a circle, turn off the lights, close the blinds, and recreate a bit of “campfire fright!” Until then, students can stream the audio at home…

This audiobook is available on Bandcamp. If you’re not familiar with that site, it’s basically a donation-based way of musicians getting their music to fans. There’s a suggested cost, usually much lower than its value, so fans can choose to throw a few more dollars towards the musicians if they want to support them a bit more. One great feature is that you can stream the tracks a few times before Bandcamp gets sad. That means students can listen to this Latin without any cost to them whatsoever! Obviously, this is a helpful option right now during remote learning. Back in the classroom, though, you might want to have the albums downloaded so you always have them ready to queue up.

Alternatively, I can send USB thumbdrives with any (or all) of the audio on them. Find those on my Square site with discounts for packs and sets, here.

New Audio Albums

For a few years now, there have been three different kinds of audio albums available: an audiobook for Rūfus et arma ātra, a complete Latin learning course for Agrippīna: māter fortis, and rhythmic accompaniment to the poetry of Pīsō Ille Poētulus. Over the past weeks, I’ve added seven additional audio albums of a fourth kind: just narration. These albums give students the opportunity to hear Latin that’s not your voice, which we know is novel in itself. When used in the classroom, these albums can also give you a break, reserving your energy for questions, etc. That’s how I’ve been using the Rūfus et arma ātra Audiobook for the past few years, and will continue to do so with the new albums. Here’s a list of what’s available:

- Rūfus lutulentus

- Syra sōla

- Pīsō perturbātus

- Drūsilla in Subūrā

- Rūfus et arma ātra (audiobook with music & sound effects)

- Quīntus et nox horrifica (audiobook with music & sound effects)

- Pīsō et Syra et pōtiōnēs mysticae

- Drūsilla et convīvium magārum

- Learning Latin via Agrippīna (Latin learning course)

- over 6 hours of Latin!

- questions and meaning established in English

- could be used independently from the book

- Pīsō Ille Poētulus (the verses with rhythmic accompaniment)

- Tiberius et Gallisēna ultima

Using Audio

Audio resources have been catching on a bit more now that remote learning plans have been rolled out. However, there are other classroom uses as well. Here’s a short list:

- Just listen!

- Listen while reading along

- Listen & Draw

- a scene

- a character

- a mashup/smashdoodle/collage of the chapter

- as evidence of understanding, learning activity, or both