Maybe having students collect, evaluate, and grade their work entirely isn’t for you. This post offers a slightly different approach with the same outcome.

Narrative accounts of student learning aren’t new. In fact, I just read about them recently in Off the Mark: How Grades, Ratings, and Rankings Undermine Learning (but Don’t Have To) One thing I haven’t heard yet is anyone combining narratives with self-grading. This would eliminate a LOT of the issues teachers have reported, namely the time it takes to score them, and the consistency needed to score them well (Schneider & Hunt, 2023).

Narratives go back about 100 years. They were the next step in efficiency following the practice of teachers visiting homes of their pupils and presenting an oral report on how the child was doing. As high school enrollment skyrocketed, though, narratives were abandoned for even more time-saving percentages, with the A-F scale in place sometime in the 40s (Brookhart et al., 2016).

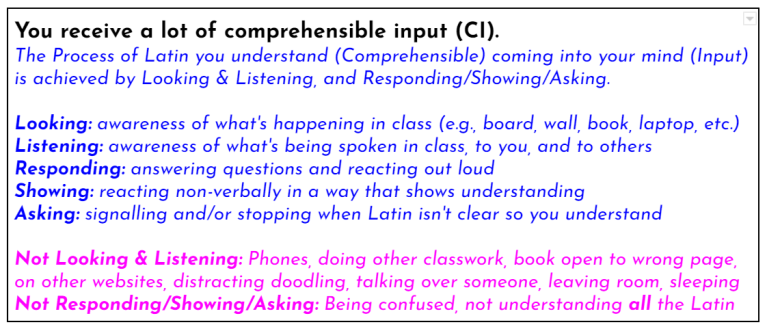

One way to resurrect narratives on a smaller scale by bringing them back into your classroom would be to a) look at students’ learning evidence, b) make a statement, and then c) have the student select a grade that they feel corresponds to what you wrote. For example, my Process criteria—one of two equally weighted categories/standards—was “you receive a lot of Comprehensible Input (CI).” That’s basically it; clear, and effective. When my students self-graded, though, I provided examples in a single-point rubric of what that could look like, as well as some non-examples to help 9th graders with some critical, evaluative thinking. Here’s a screenshot:

That worked well, but maybe you want to add a narrative account to the grading. To come up with a narrative from this criteria, let’s imagine a student missing assignments who doesn’t respond in class, and hardly ever asks Latin to be clarified. The statement could be “you’re missing learning evidence that could otherwise show you’re receiving CI. In class, you rarely show understanding, and hardly ever ask for Latin to be clarified.” Then, the student would select a grade on the 6-point scale (55, 65, 75, 85, 95, 100). If they say something like “85,” just follow up and talk about how missing assignments and rarely meeting expectations surely isn’t something represented by that number. If they say “75,” or “65,” that sounds about right depending on the degree of what is/isn’t happening.

This doesn’t have to be rocket science.

We already know that the more students think about how well they’re doing something, the worse they actually end up doing (Kohn, 1993), so limiting this exchange to once a quarter reduces any negative impact to to a minimum. Overall, this practice might be worth trying for teachers who want to retain a bit of control while still being in pursuit of getting scores and points mostly out of the picture.