I left my 2025 MTA Summer Conference workshop participants with a LOT of resources to read. After getting through all the recommended posts and maybe even books, however, they’ll probably still face the question of “what do I DO?!” The answer to that shouldn’t be a one-size-fits all panacea, but I can definitely offer some guidance since there are relatively few moves to make in the pursuit of grading less…

Continue readingself-assess

READ THIS: Blum’s “UNgrading…”

Rereading the preface to this book was a little depressing. The first time I read it over three years ago, I had highlighted “but should we, assuming an end to the lockdown, just go back to business as usual? What if the usual is problematic?” (p. xxii). At the time, I was experiencing “business as usual” despite a glimmer of hope between spring 2020 and 2021 when it looked like grading practices were going to shift in a massive way. They did not.

Continue readingREAD THIS: Dylan Wiliam’s “Embedded Formative Assessment”

I had the opportunity to revisit Wiliams’ 2018 book, Embedded Formative Assessment, while looking for definitions of “formative assessment.” The first two chapters are simply priceless. Beyond those, the other chapters include a general problem to be solved, and then practical techniques on solving them. Here’s an overview of what I consider the best parts…

Continue readingREAD THIS: Sackstein’s “Hacking Assessment” (2nd Ed.)

In getting ready for my 2025 MTA Summer Conference presentation on “Getting More from Your Formative Assessments and Grading,” I found a lot more missing blog posts than just Zerwin’s! For example, I never wrote about Starr Sackstein’s “Hacking Assessment…” years back; there’s good stuff in there, which means I need a record of that stuff here.

Continue readingREAD THIS: Zerwin’s “Point-Less…”

In cobbling together sources for my 2025 MTA Summer Conference presentation on “Getting More from Your Formative Assessments and Grading,” I searched my blog to link posts on books I consider foundational. Somehow, I never published the post I wrote after reading Zerwin’s “Point-less” years back. Her work deserves some attention…

Continue readingFalse Formatives

Click here for the updated model and latest research.

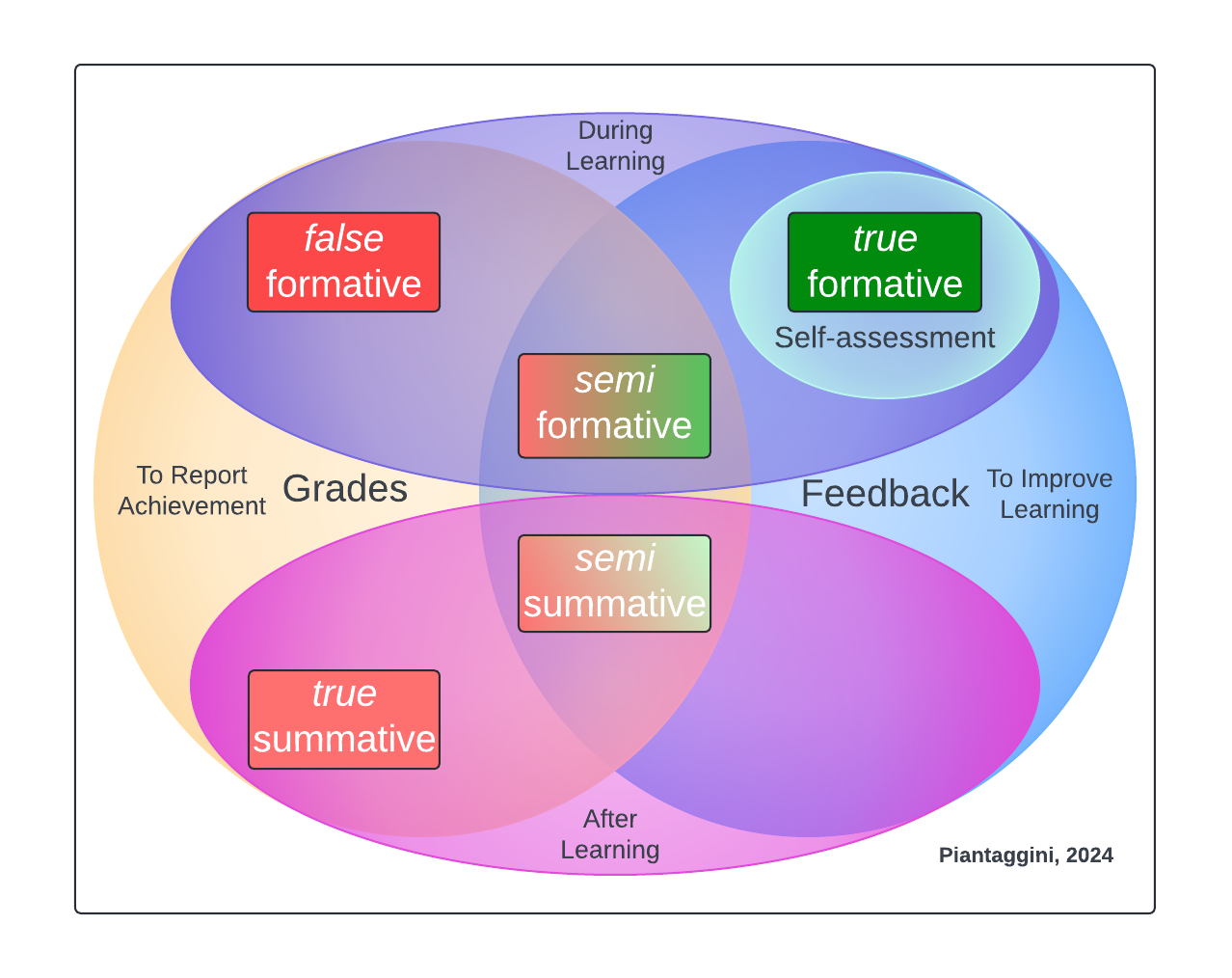

I just presented a poster session in Chicago for the NCME Special Conference on Classroom Assessment (Piantaggini, 2024). While I had some rough details for a proposed dissertation study, the focus of discussion with scholars who stopped by was my new assessment model and the theoretical framework that brought me to it. The message I got was “I think you’re onto something,” so I’m sharing my work here to get more eyes on it. Please contact me with any embarrassingly scathing criticism. Otherwise, reply publicly with any other thoughts or questions. After all, this is my blog, not peer review!

So, in this blog post, I’ll describe the model you see above, and how I got there, starting with a major dilemma I identified when reviewing literature on classroom assessment: confusion over grading formative assessments…

Continue readingStudent-Led Assessment (Published!)

This is my first contribution to a major publication for all teachers—not just those teaching Latin—since I officially began researching grading practices at UMass. I’ll get to what you’ll find from me in Starr’s book later, but I just received my copy and wanted to share some top reasons why you probably want this book…

Continue readingSorting vs. Grading: How To Properly Use Standards

Years back, I wrote about how a standards-based model to learning and grading (SBG) fell short of the bar. This was true of a particular kind of SBG—the kind with 10-30 standards being tested and graded every single quarter, scheduling multiple reassessments for each one, and still using scores of 1-4 in a way that keeps focus on points (not learning). The good news is that not all models are like that. The bad news is that a LOT of them are, which in turn give standards and accompanying practices a bad name. Teachers end up hating SBG, and admin scrap plans for any schoolwide change.

To be clear, I’m more of a “burn it to the ground” kind of guy, advocating for little to no grading whatsoever, but I’ve also found that a basic understanding of standards is crucial to ungrading. In fact, I’m not sure you can do it without standards…

Continue readingTeacher Narratives + Student Self-Grading

Maybe having students collect, evaluate, and grade their work entirely isn’t for you. This post offers a slightly different approach with the same outcome.

Narrative accounts of student learning aren’t new. In fact, I just read about them recently in Off the Mark: How Grades, Ratings, and Rankings Undermine Learning (but Don’t Have To) One thing I haven’t heard yet is anyone combining narratives with self-grading. This would eliminate a LOT of the issues teachers have reported, namely the time it takes to score them, and the consistency needed to score them well (Schneider & Hunt, 2023).

Narratives go back about 100 years. They were the next step in efficiency following the practice of teachers visiting homes of their pupils and presenting an oral report on how the child was doing. As high school enrollment skyrocketed, though, narratives were abandoned for even more time-saving percentages, with the A-F scale in place sometime in the 40s (Brookhart et al., 2016).

One way to resurrect narratives on a smaller scale by bringing them back into your classroom would be to a) look at students’ learning evidence, b) make a statement, and then c) have the student select a grade that they feel corresponds to what you wrote. For example, my Process criteria—one of two equally weighted categories/standards—was “you receive a lot of Comprehensible Input (CI).” That’s basically it; clear, and effective. When my students self-graded, though, I provided examples in a single-point rubric of what that could look like, as well as some non-examples to help 9th graders with some critical, evaluative thinking. Here’s a screenshot:

That worked well, but maybe you want to add a narrative account to the grading. To come up with a narrative from this criteria, let’s imagine a student missing assignments who doesn’t respond in class, and hardly ever asks Latin to be clarified. The statement could be “you’re missing learning evidence that could otherwise show you’re receiving CI. In class, you rarely show understanding, and hardly ever ask for Latin to be clarified.” Then, the student would select a grade on the 6-point scale (55, 65, 75, 85, 95, 100). If they say something like “85,” just follow up and talk about how missing assignments and rarely meeting expectations surely isn’t something represented by that number. If they say “75,” or “65,” that sounds about right depending on the degree of what is/isn’t happening.

This doesn’t have to be rocket science.

We already know that the more students think about how well they’re doing something, the worse they actually end up doing (Kohn, 1993), so limiting this exchange to once a quarter reduces any negative impact to to a minimum. Overall, this practice might be worth trying for teachers who want to retain a bit of control while still being in pursuit of getting scores and points mostly out of the picture.

Self-Grading: Explained

Is self-grading effective, and worth it? All signs point to “yes.” Some research findings appear at the end of this post.

Along with the minimum 50, self-grading is another high-leverage practice often found in an ungrading approach that keeps the focus on learning. In practice, though, self-grading is often misunderstood. If anyone hears about students giving themselves a grade and imagines a kid with their head on the desk all quarter who suddenly pops up and says “I get an A,” that’s dead wrong. With a solid self-grading practice that maximizes teacher prep time and empowers students to evaluate their learning, this student would lack evidence to make such a claim. And that’s one focus of this post (i.e., making a claim). Let’s first start with what teachers have been doing—historically—to make a claim about students’ grades so we can explain self-grading…

Continue reading