Instances of Latin shaming (i.e. causing one to feel ashamed or inadequate regarding their use of Latin) come up every now and then. I last pondered the issue back in August of 2019 in a draft of this post, first started in 2018 after observing some kind of online scuffle. Like clockwork, there have been public discussions once again regarding Latinity (i.e. quality of Latin), whether spoken in the classroom, or appearing in published works. To be clear, I have no interest in participating in those discussions. None. However, I’d like to share a bit about what’s been going on, and give some examples of Latin shaming…

Continue readingAuthor: magisterp

Rejoinders: Teacher vs. Students

This year, I’ve begun each quarter by sharing new (or “new”) expectations. These are simple reminders of rules and routines expressed in a slightly different way to keep management tight. For example, Q2 featured “less English, more Latin” to address increased chatter from students becoming more comfortable. This week, I introduced Q3 with “mostly Latin, almost no English.” However, I still don’t require or expect students to speak Latin (i.e. forced output). Here’s how that works…

Continue readingAP Latin: There’s Bad News…And…Worse News

**Related: Revised AP Latin 2025**

I ran texts from the AP Latin syllabus through Voyant Tools:

- 6,300 total words in length

- 2,800 forms (i.e. aberant + abest = 2)

- 1,100 meanings/lemmas (i.e. aberant + abest = 1 meaning of “awayness”)*

Based on the research of Paul Nation (2000), 98% of vocabulary must be known in order to just…read…a text. According to Nation’s research, then, Latin students must know about 6,175 words they encounter in the text in order to read the AP syllabus texts. That’s a text written with 1,100 words. To put that into perspective, it’s been reported that students reasonably acquire ~175 Latin words per year, for a total of something more like 750 by the end of four high school years. Needless to say, there’s a low chance that all 750 would be included the Latin on the AP, and that varies from learner to learner. Even if they were, though, 750 is still only 68% of the vocabulary at best. Although this percentage isn’t the same as text coverage since it doesn’t account for how many of the 1,100 words repeat, it’s safe to say that the number isn’t going to be wildly higher. Even approaching 80% text coverage is not good. We know that reading starts to get very cumbersome below 80%. This is just one reason why no student can actually read AP Latin. Oh wait…

****Those figures are just for Caesar****

Continue readingDemonstrations: Providing Compelling Input

I’ve known that Krashen et al. suggested long ago that using Total Physical Response (TPR) to teach basic dance steps, martial arts, magic tricks, etc. results in compelling input. I’ve seen presenters talk about the idea of doing so, but haven’t really seen it much in classrooms. Now, I’ve performed one of Eric Herman’s magic tricks, but I didn’t really think I knew how to do anything that I could instruct students to do.

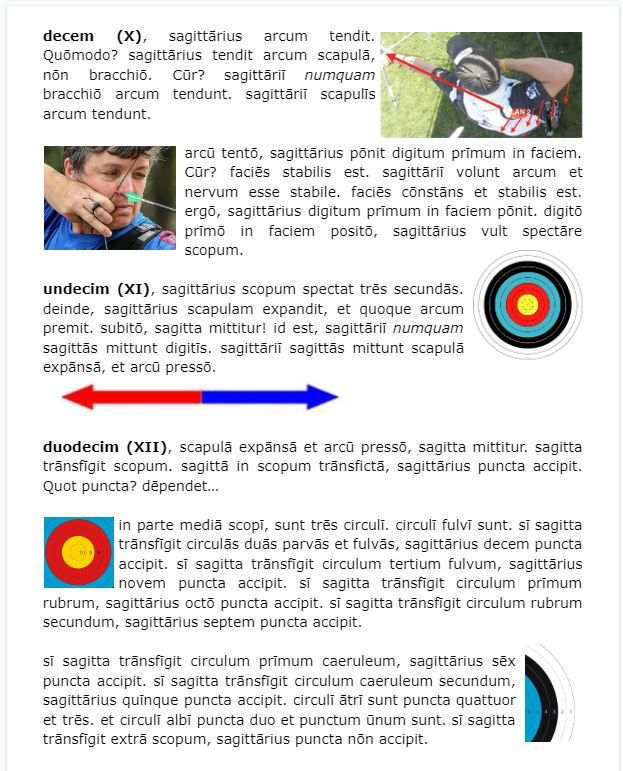

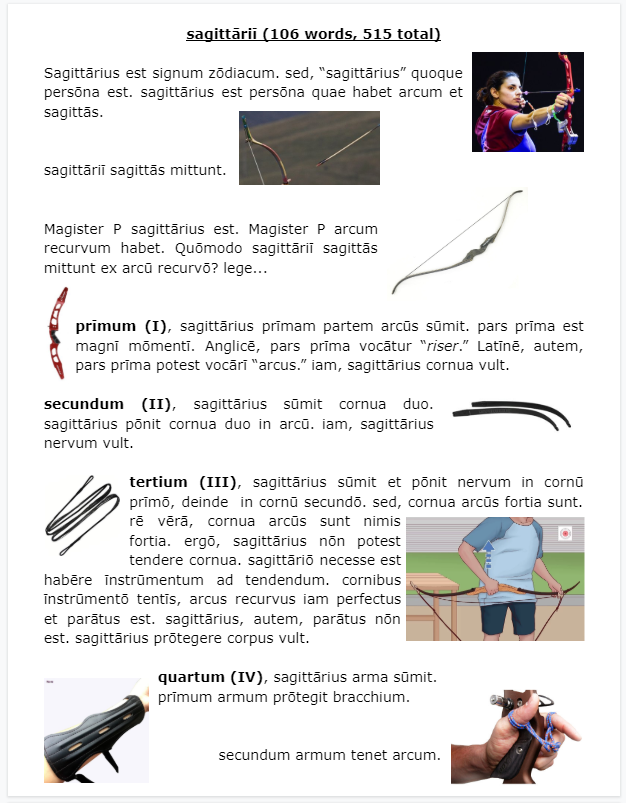

However, Tuesday was one of those perfect times to try something new during a weird day because the rest of the week was midterms. Since I got into archery this year, I decided to bring in my bow to demonstrate basic assembly, shot cycle, and target point values. Yes, I cleared this with security as well as admin, and no, I didn’t bring any arrows.

The experience was fantastic.

Students were captivated for a solid 45 minutes, and there’s no surprise why. Humans are naturally curious learners. It’s just that the school system has destroyed the joy of learning. If we can pause that “school feeling” for a moment, we bring back the joy. After my demo using common vocab, I projected a list of archery-specific phrases, and we co-created a quick text on archery. From there, I put together a more comprehensive packet. However, I wasn’t teaching words. I was teaching about archery. That’s the content.

In pedagogical terms, this is content-based instruction (CBI). Students asked a lot of questions about the bow. Why? It’s cool. In comparison, though, they didn’t ask as much about Roman apartment buildings last month. Why? That’s kind of boring, no matter how well we connect the content to their lives. Of course, exploring Roman content works the same way as exploring archery. It’s just that it takes someone with particular interests to get as excited about Romans. However, I’m not convinced that this should be either/or. I’ll both continue to explore Roman content (in Latin), as well as teach about other content (in Latin).

I’m now looking for other things to demo. Drumming might be one. After performing that card trick, I suppose I could teach it. In all of this, I’m reminded of how beneficial it is to include students in the demo process (e.g. distribute toy bows, drum sticks, decks of cards, etc.).

So, What could you teach your students?

The Latin Problem

According to the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), there’s a scale of five main proficiency levels: Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, Superior, and Distinguished. Most states require Advanced Low speaking proficiency to teach modern languages. However, many teachers attain near-native-like proficiency, anyway. To give you a sense of what that means, beyond Advanced Low, there’s still Advanced Mid, Advanced High, Superior, and then the highest rating on the ACTFL scale, Distinguished, for which the following are features:

“A non-native accent, a lack of a native-like economy of expression,* a limited control of deeply embedded cultural references, and/or an occasional isolated language error may still be present at this level.”

*economy of expression

“The use of the most precise and expressive words and phrases, thus eliminating the need for excess description, wordiness, jargon, or circumlocution.”

Of course, most of these teachers spend time abroad, and/or have found themselves exposed to the target language in some other way. Needless to say, modern language teachers tend to be highly proficient speakers, yet at the same time they’re not necessarily scholars who study the language, earning an M.A. in its literature. Granted, it’s not uncommon for modern language teachers to be that kind of scholar while also studying abroad and/or being exposed to input and interaction elsewhere. However, the former certainly isn’t necessary in order to achieve the latter. Then there’s the Latin problem…

Continue readingVocab Overload

This is the time of year when it becomes obvious how much students have not acquired. That is, words not even remotely close to the most frequent of the most frequent are almost completely incomprehensible when they appear in a new text.

That’s OK.

Perhaps you’ve already experienced this earlier in the year. Perhaps it’s coming. Either way, it’s important to recognize that falling back to the old mindset of “but we covered this?!” is *not* going to fly in a comprehension-based and communicative language teaching (CCLT) approach. To clarify: understanding in the moment is CI, and exposure to CI over time results in acquisition. For example, a text so comprehensible that all students can chorally translate it with ease one class might have a handful of topic-specific vocab. Even though there could be an entire class, maybe even an entire week of exposure, topic-specific vocab that isn’t recycled throughout the year has a very low chance of being acquired and comprehended in new texts. **Therefore, students can experience vocab overload even in classes with high levels of CI.** That applies to “big content words,” like all the vocab needed to talk about Roman kings. Now consider function words, like adverbs, conjunctions, particles, etc. that hold very little meaning on their own. Those have almost no chance of being understood unless they keep appearing in texts.

Of course, we cannot recycle all previous words in every new text, which is why acquisition takes so long. Naturally, the least frequent words fall off and out of bounds, and only the most spongiest of memory students have a shot at acquiring those. However, we cannot expect from most students what only few can do. Instead, we must expect will happen when vocab spirals out beyond the possibility of being recycled, and address that before it happens. Here are ways to address vocab overload when providing texts:

- Dial things back as much as you can, focusing on the top most frequent & useful words.

- Write a tiered version, or embedded reading for every new text, even if that new text is very short.

- When possible, use a word more than once, and in different forms. Fewer meanings (e.g. ran, runs, will run, running) have a greater chance of being understood than many meanings focused on a grammar feature (e.g. ran, ate, laughed, said, carried, was able, were).

- If a function word is important, use it a lot (e.g. the more recent “autem” has no chance of being understood if you keep using “sed”).

- If a message can be expressed in one very long sentence, break it into two or more shorter ones, restating subjects, etc. for clarity. Then, repeat the full message with a function word (e.g. “therefore,…so…”).

- When expanding vocabulary with synonyms, especially when beginning with cognates, consider glossing with the previous (e.g. if you began the year with “studēns,” each text that now has “discipula” could have ( = studēns) after the first instance in that text. Continue using “discipula,” but use “studēns” to clarify meaning when needed).

Full Weeks Of School? Not As Many As You Think!

The winter months are notorious for their interruptions, such as midterms/finals, PD days, holidays, and [un]expected bad weather. We’re back from the longest break, but not in full swing, and don’t expect to be. Why? I’ve long observed how Thanksgiving vacation marks the end of the most productive time of school, and the Swiss cheese feeling we’re in from now through February leaves just a couple months left to finish out the year. That is, with April vacation and a handful of other random short weeks of teaching, the next 18 weeks of instruction are going to fly by.

So, I took a look at all the interruptions throughout the year. Surprisingly, only 75% of the weeks are a full five days. That means 1/4 of the time teaching, plans based on an entire week’s worth of activities and routines get all messed up…for the entire year! Now, anything that messes things up as often as 25% of the time is enough to lead to burnout. There are a number of ways to plan no- to low-prep, and avoid that burnout, but for the 25% of short school weeks, perhaps the best way is to treat daily routines as independent from one another, not always needing the previous day’s events (e.g. a Tuesday routine shouldn’t rely on whatever happens Monday).

This is just a reminder to plan wisely (i.e. smarter, not harder) for the second half of the year!

Total Words Read

Last year, I reported total words read up to holiday break, and it’s hard to believe that time of year is upon us again. Since part of my teacher eval goal is to increase input throughout the year, let’s compare numbers. 2018-19 students read over 20,000 total words of Latin by this time. However, this year’s students have read…uh oh…just 11,000?!?!

Hold up.

Something’s going on. I’m positive that students are reading more now, and for longer periods of time. Classes are now structured to be roughly half listening and half reading (i.e. Talk & Read), too. So…why don’t the numbers add up?! Surely there’s a reason. Let’s look into that, starting with this quote from last year’s post:

“Over the 55 hours of CI starting in September up to the holiday break, students read on their own for 34 total minutes of Sustained Silent Reading (SSR), and 49 minutes of Free Voluntary Reading (FVR)…“

This year’s independent reading time has skyrocketed to 99 and 233. That’s nearly 5x more independent choice reading! Now, last year’s 20,000 figure included an estimated 1,900 from FVR. Therefore, it’s not unreasonable to estimate that this year’s students have read something like 9,500 total words during FVR, which would be like reading a third of this paragraph worth of Latin per minute. If so, the year-to-year comparison would be very close (i.e. 20,000 vs. 20,500). However, I’d expect the numbers to be much higher now with even more of a focus on reading. Seeing as it’s really difficult to nail down a confident number during independent choice reading due to individual differences, then, let’s just subtract all that FVR time from both years, arriving at 18,100 to compare to this year’s 11,000, which is still quite the spread. Let’s do some digging…

Continue readingInput Hypermiling: StoryGuessing

Weeks ago, I wrote about the super fast process of collaborative storytelling, StoryGuessing. A year ago, I began looking for ways to hypermile classroom input. Here’s how to combine the two…

Continue readingPīsō et Syra et pōtiōnēs mysticae: The Cognate Book Published!

This novella is written with 163…COGNATES!

That’s right.

There are 163 fairly to super clear Latin to English (and even Spanish) cognates, and then just 7 other necessary Latin words (ad, est, et, in, nōn, quoque, sed) found within this tale of nearly 2500 words in length.

“Piso can’t seem to write any poetry. He’s distracted, and can’t sleep. What’s going on?! Is he sick?! Is it anxiety?! Has he lost his inspiration?! On Syra’s advice, Piso seeks mystical remedies that have very—different—effects. Can he persevere?”

Pīsō et Syra… is the 17th novella in the Pisoverse, the collection of Latin novellas written with sheltered (i.e. limited) vocabulary to provide more understandable reading material for the beginning Latin student. The Pisoverse now provides over 44,000 total words of Latin using a vocabulary of 645 (just about half of which—320—are cognates!).

1) Pīsō et Syra et pōtiōnēs mysticae is now available on Amazon.

2) For Sets, Packs, and Bundle Specials (up to $200 off!), order here.