I’ve been sitting on this post for a very, very long time, perhaps because I hadn’t been entirely confident in my review of classroom assessment literature enough to make a claim about standards-based grading (SBG) that isn’t exactly positive. In short, the literature suggests that practices most likely to support learning are achieved by keeping graded summative assessments to a minimum.

SBG might not be doing this.

While some SBG systems use a 0-4 scale to report achievement, others use an ordinal scale, with words like “proficient” replacing “A” or “95” (Townsley, 2022). The thing is, though, these words are still grades. Like all grades, they are symbols representing levels of student performance (Brookhart et al., 2016).

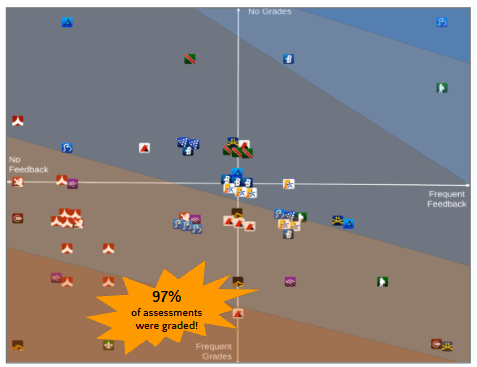

Unfortunately, grades have a damning history with unreliability and variability, undermining teachers’ feedback, and students’ negative associations with motivation. We’re not talking about a few studies here and there, either. We’re talking about 35+ studies spanning 115 years from Meyer (1908) to Mandouit & Hattie (2023). I even found something similar in my own pilot study conducted last year in a small rural high school in New England. Surveys and assessment samples from 15 teachers and interviews from seven students showed an extremely high frequency of grading, and negative effects of the lack of feedback. Most teachers in the study (87%) were using SBG.

Figure 1. Each icon represents a different teacher, their assessment type(s), and each assessment’s qualities, such as occurrence throughout the semester, learning cycle timing, feedback frequency, and grading frequency. The dark blue overlay in the upper right corner represents frequent feedback and no grades. The dark orange overlay in the lower half represents frequent grades and no feedback. The broad band with no overlay running between each extreme represents more of a neutral combination of characteristics, such as graded assessments with feedback, but not occurring frequently enough to have either benefit of feedback or drawback of grades. The cluster of icons in the center shows that the majority of teacher assessments had a mix of grades and feedback, with either a neutral to negative impact on learning (Piantaggini, 2025).

Too Much Grading

If grades were seen by students only occasionally here and there, that would be a different story. In most SBG systems, however, grades are constantly being reported on assessments throughout the learning process as teachers look to assess and reassess students against each standard.

For example, a teacher determines that a student’s work shows “developing” according to the department’s rubric. The teacher then marks it as such in the gradebook (i.e., a summative function), then schedules some reteaching, or provides enrichment, and then reassesses. After these adjustments, the student shows “meeting” the standard on the next assessment, and the grade is updated. The more this happens, though, the more students are being graded, which has not been shown to be an effective practice for improving learning. Even alongside feedback, the negative effects of grades take over (Butler & Nisan, 1986; Butler, 1987; Butler, 1988; Cardelle & Corno, 1981; Elawar & Corno, 1985; Koenka et a., 2021; McLaughlin, 1992).

It turns out that we have some comparative quantitative findings on this specifically with SBG, too. Townsley & Varga (2018) filled a gap in the literature by comparing, GPA, ACT scores, and traditional vs. SBG grading between two similar high schools. Results showed that there was no difference in GPAs, and ACT scores were lower in the SBG group.

Why might SBG not be as effective?!

My hypothesis is that in Townsley and Varga’s study, even though traditional grading should have been less effective, students in that system might have seen grades just once every week with little to no opportunity to revise. In the SBG school, however, students getting anything less than the highest rating would have been reassessed in order to show understanding at the highest level. The result might have meant more grades more often than the traditional system?! Of course, this is untested. In a study like Townsley and Varga’s, I would want to know how many grades students in each school received, and/or how often they received them.

Summary & Solutions

SBG is a system attempting to address long-standing issues with grading, but it might not be enough. It’s more likely that using a particular grading system is less important than how much the system allows for practices that keep graded summative assessments to a minimum. SBG, alone, cannot do this.

The most promising solutions I’ve seen so far—within any grading system—would be to use portfolios for students to gather learning evidence + self-grading at progress reports and report cards, limiting grades to just 8x/year in a quarter system. Otherwise, all work throughout the learning process is marked as collected (or missing, late, etc.) in the gradebook, and the teacher gives feedback on how to improve, provides follow-up opportunities for students to apply that feedback, and the cycle continues until it’s time to report achievement, however the school has established that timeline (e.g., quarters, trimesters, semesters, etc.).

References

Brookhart, S. M., Guskey, T. R., Bowers, A. J., McMillan, J. H., Smith, J. K., Smith, L. F., Stevens, M. T., & Welsh, M. E. (2016). A Century of Grading Research: Meaning and Value in the Most Common Educational Measure. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 803–848. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316672069

Butler, R., & Nisan, M. (1986). Effects of no feedback, task-related comments, and grades on intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(3), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.78.3.210

Butler, R. (1987). Task-involving and ego-involving properties of evaluation: Effects of different feedback conditions on motivational perceptions, interest, and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 474–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.79.4.474

Butler, R. (1988). Enhancing and Undermining Intrinsic Motivation: The Effects of Task-Involving and Ego-Involving Evaluation on Interest and Performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 58(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1988.tb00874.x

Cardelle, M., & Corno, L. (1981). Effects on Second Language Learning of Variations in Written Feedback on Homework Assignments. TESOL Quarterly, 15(3), 251.https://doi.org/10.2307/3586751

Elawar, M. C., & Corno, L. (1985). A Factorial Experiment in Teachers’ Written Feedback on Student Homework: Changing Teacher Behavior a Little Rather Than a Lot. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 162–173.

Koenka, A. C., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Moshontz, H., Atkinson, K. M., Sanchez, C. E., & Cooper, H. (2021). A meta-analysis on the impact of grades and comments on academic motivation and achievement: A case for written feedback. Educational Psychology, 41(7), 922–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1659939

Mandouit, L., & Hattie, J. (2023). Revisiting “The Power of Feedback” from the perspective of the learner. Learning and Instruction, 84, 101718.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101718

McLaughlin, T. F. (1992). Effects of Written Feedback in Reading on Behaviorally Disordered Students. Journal of Educational Research – J EDUC RES, 85, 312–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1992.9941131

Meyer, M. (1908). The Grading of Students. Science, 28(712), 243–250.

Piantaggini, L., (2025, May 14). Captives: Students and Teachers Held Hostage By Graded Formatives [Poster session], University of Massachusetts College of Education Annual Research Showcase, Amherst, MA.

Townsley, M., & Varga, M. (2018). Getting High School Students Ready for College: A Quantitative Study of Standards-Based Grading Practices. Journal of Research in Education, 28(1), 92–112.

Townsley, M. (2022). Using Grading to Support Student Learning (1st edition). Routledge.

Lance,

As I read Brookhart and colleagues (2016) review of a century of grading research, the following summarizing quote stands out: “This review suggests that most teachers’ grades do not yield a pure achievement measure but are rather a multidimensional measure dependent on both what the students learn and how they behave in the classroom” (p. 835). In other words, traditional grading practices that rely upon mere point accumulation do not often accurately communicate learning because more than just summative evidence contributes to the final grade (see a model of point accumulation learning on p. 11 from Townsley, 2022). *Theoretically*, standards-based grading (a model of grading to support student learning, p. 91, Townsley, 2022) communicates students’ current level of learning based upon (typically the most recent) summative evidence. Related to the aforementioned Townsley & Varga (2018) and other studies that may not fully align with this theoretical construct, fidelity of implementation is a legitimate concern! See Guskey and Link (2022) for suggestions that standards-based grading has been loosely defined and Townsley and Wilcox (2024) for possible SBG defining criteria.

Further, as Wiliam (2020) contends: “There will never be a perfect grading system. Any system will be the result of a messy series of trade-offs, between how well the grades describe the students’ work and how people react to those grades, between precision and accuracy, between the short-term and the long-term, and so on.”

https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/avoiding-unintended-consequences-in-grading-reform

https://tguskey.com/wp-content/uploads/TIP-22-Is-Standards-Based-Grading-Effective.pdf

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00098655.2024.2357615

I value your thinking on this blog!

-Matt

Nice; thanks for the ~Varga catch (oops!), plus those links. They’ve gone right into my Zotero “To Read” folder (along with several I snagged from your recent blog post). Of the 22 in there right now related to classroom assessment and grading, 14 are from this past year?!

I agree that SBG is theoretically leagues ahead of other messy systems (re: Wiliam, 2020). In practice, though, I’m still concerned with the constant barrage of grades. It’s often just…a ton…of grades under the guise (oooh, scandalous) of getting learners to meet those standards. Now, if there were teachers using standards to provide feedback and involved learners in follow-up opportunities to revise, etc., and truly limited the grading of those standards to a handful of times a year, now we’re talking! I haven’t seen it work like that, though. Have you?

I see a couple of themes here to further explore: frequency of grade book entries, number of standards, and fidelity of implementation.

Frequency of grade book entries: Regarding a “barrage of grades,” I agree that implementing standards-based grading could/would be easier without the expectations of regularly communicating student learning via electronic grade books that are accessible to parents and students. In other words, if the expectations was to only communicate where a student was at in relation to the standards at the end of each reporting period, then frequent grade book entries for each standard would not be needed. I have seen this take place in some elementary settings where parents and students do not have access to an electronic grade book and standards are reported at the end of each reporting period. In middle and high school settings, I have not seen this in practice much do the expectations in place to regularly update the electronic grade book.

Number of standards: I think in the ideal world, students would be taught and assessed every state standard in every content area; however, a while back, Marzano and colleagues (and perhaps others) have suggested there is not enough instructional time to do so. This may be one of the reasons some authors suggest “priority” or “power” or “essential” standards in the context of a guaranteed and viable curriculum. Still other authors suggest lumping standards together to establish broad progress report card statements. Again, limiting the grading of these standards to a handful of times per year (see Frequency of grade book entries above) will be dependent upon the number of standards taught/assessed as well as the expectations of updating an electronic grade book. (please correct me if I misinterpreted your implication of fewer standards).

Fidelity of implementation: In addition to the discussion within the two previous themes, I agree there are plenty of schools that are still seeking to better implement standards-based grading, and of course a small number that may be misguided in their intended implementation as well. We have been hosting a leadership-focused standards-based grading conference here in Iowa (https://coe.uni.edu/llc/about-department/institute-educational-leadership/standards-based-grading-conference) for past couple of years and I have been impressed with those in attendance seeking to raise the bar in their implementation efforts!

re: middle/high school expectations to update gradebook as obstacle to reporting grades less often, In my classroom teaching experience I found that admin, parents, and students were mostly just looking for information and record-keeping (rather than reporting achievement). Gradebook assignments just had symbols to convey status like “missing,” “late,” “incomplete,” or “collected,” and any feedback was on the assignment itself (i.e., Gradebook description, or in something like Google Classroom that was used to assign/submit). No grades. No scores. The grades for assessed standards were just reported 8x (progress reports, and end-of-quarter). Would love to do research on this model.

re: number of standards, I’m definitely in agreement. Way too many to be grading, but yes, I did mean “limiting the grading of standards” to mean something more like what I wrote just now about only reporting grades ~8x/year. Still plenty of gradebook info (i.e., “collected,” “missing,” etc.), just fewer grades in the whole equation.