This is an update to my 2024 presentation and assessment model reflecting insights from a continued review of classroom assessment and grading literature, findings from a new pilot study, and a novel framing of the formative assessment process I call Guidance Phases. Here’s a summary of the updates:

- A few literature sources removed; many new ones added

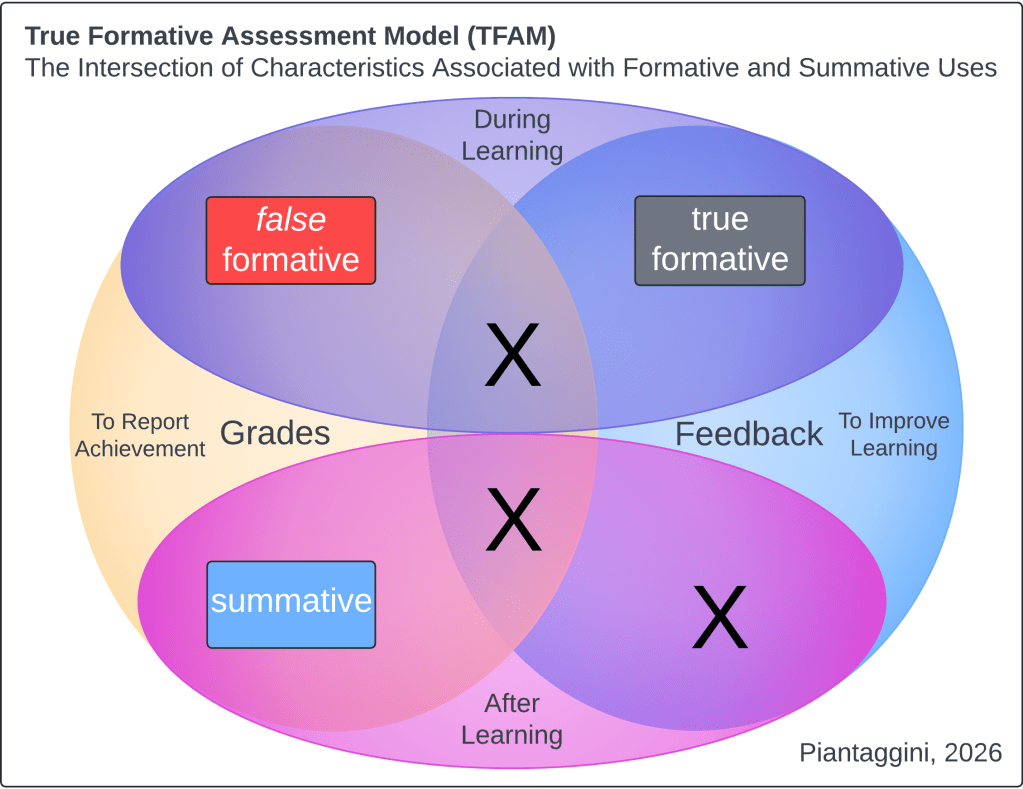

- The labeling and categorizing of assessments that mix characteristics has been abandoned to keep the focus on avoiding false formatives and incorporating more true formatives.

- Rather than a characteristic, the role of self-assessment has been expanded to fall under Guidance Phases as part of the feedback cycle; it no longer appears in the Venn diagram.

- Assessments, themselves, cannot be formative or summative. It is the use that determines one or the other. Therefore, I’ve clarified that the terms “formative” and “summative” in this model refer to characteristics. For example, a true formative is an assessment used in a formative way as seen through its associated characteristics (and not other characteristics associated with a summative use).

True Formative Assessment Model (TFAM)

This is the name of my model using a Venn diagram to show the intersection of assessment characteristics associated with formative and summative uses: