My recent review of assessment has continued, which now includes two major findings:

- Grading is a summative function (i.e., formative assessments should not be graded).

(Black et al., 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Bloom, 1968; Boston, 2002; Brookhart, 2004; Chen & Bonner, 2017; Dixson & Worrell, 2016; Frisbie & Waltman, 1992; Koenka & Anderman, 2019; Hughes, 2011; O’Connor et al., 2018; O’Connor & Wormeli, 2011; Peters & Buckmiller, 2014; Reedy, 1995; Sadler, 1989; Shepard et al., 2018; Shepard, 2019; Townsley, 2022)

- Findings from an overwhelming number of researchers spanning 120 years suggest that grades hinder learning (re: reliability issues, ineffectiveness compared to feedback, or other negative associations).

(Black et al., 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Brimi, 2011; Brookhart et al, 2016; Butler & Nisan, 1986; Butler, 1987; Cardelle & Corno, 1981; Cizek et al., 1996; Crooks, 1933; Crooks, 1988; Dewey, 1903; Elawar & Corno, 1985; Ferguson, 2013; Guberman, 2021; Harlen, 2005; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Johnson, 1911; Koenka et al., 2021; Koenka, 2022; Kohn, 2011; Lichty, & Retallick, 2017; Mandouit & Hattie, 2023; McLaughlin, 1992; Meyer, 1908; Newton et al., 2020; O’Connor et al., 2018; Page, 1958; Rugg, 1918; Peters & Buckmiller, 2014; Shepard et al., 2018; Shepard, 2019; Starch, 1913; Steward & White, 1976; Stiggins, 1994; Tannock, 2015; Wisniewski et al., 2020)

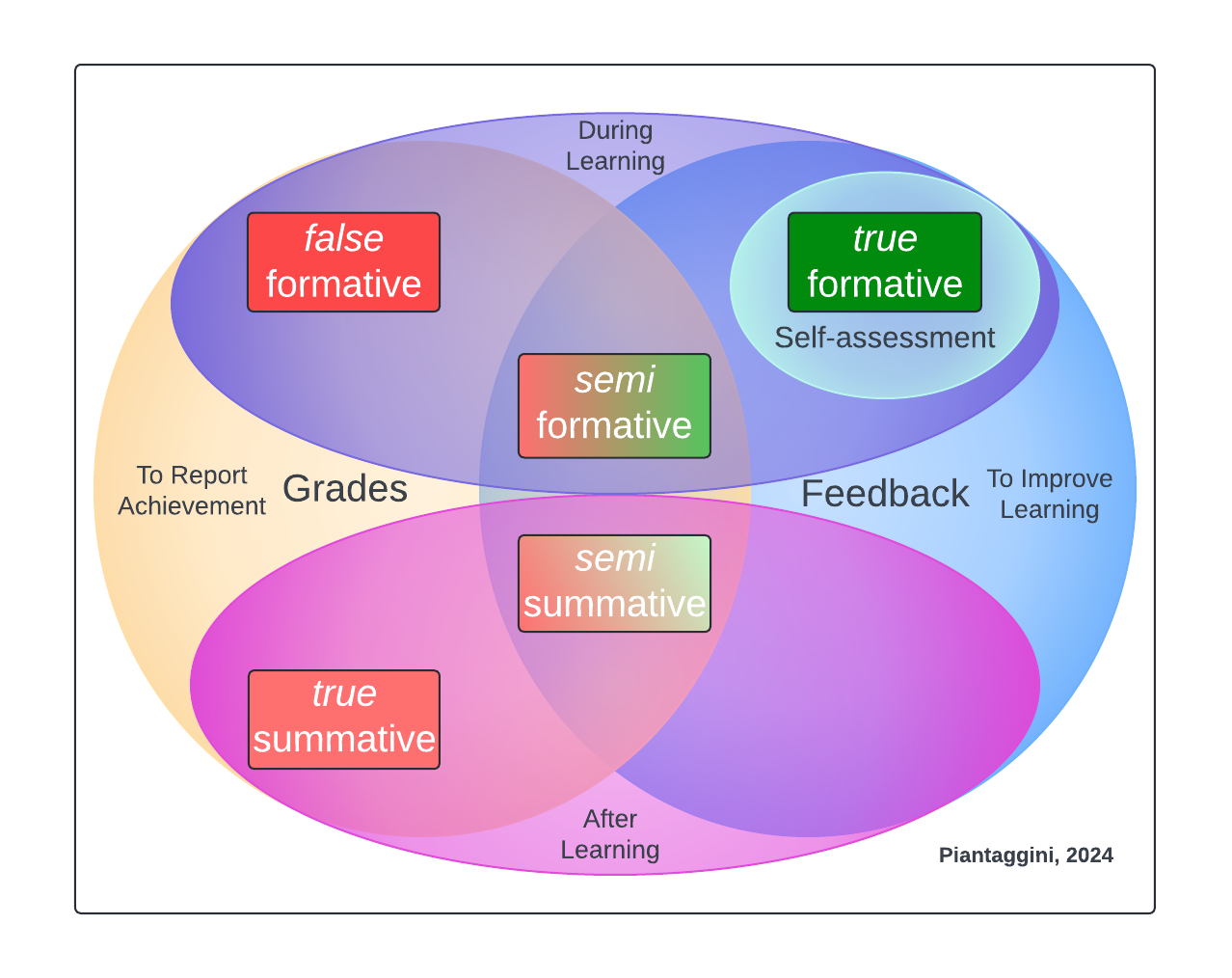

In other words, 1) any assessment that a teacher grades automatically becomes summative, even if they call it “formative” (I’m referring to these as false formatives), and perhaps more importantly, 2) grades get in the way of learning. These findings suggest that best way to support learning is by a) limiting grading to only true summative assessments given at the end of the grading period (e.g., quarter, trimester, semester, academic year), and b) using alternatives to grading formative assessments that otherwise effectively make them summative. Therefore, my next stage of reviewing literature focuses on reducing summative grading and exploring formative grading alternatives (i.e., so they remain formative). As for now, one of those practices *might* be retakes, which has been on my mind ever since I saw a tweet from @JoeFeldman. Given the findings above, which establish a theoretical framework to study grading, let’s take a look at how retakes are used now, and how they could be used in the future, if we even need them at all…

Continue reading →