You might have caught my variation on Martina Bex’s Word Race. While students certainly were hearing more target language, there were too many that went by too quickly while reading with enough repetition for the novice. Well, here’s an update that reaaaaaally gets students listening to the target language in a more structured, less-harried way:

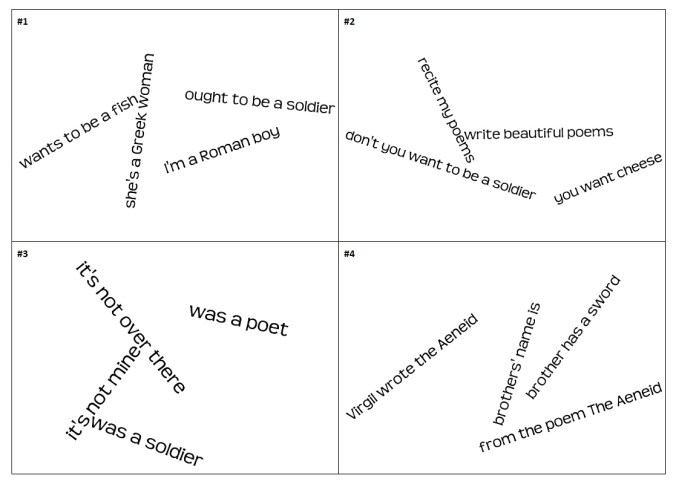

- Instead of one large word cloud with many English phrases from the text, create 4 smaller ones that each contain one true phrase from the text, and three other phrases. I’ve been doing 1 funny phrase, 2 possible phrases, and the 1 from the text itself.

- You still read the text out loud as usual.

- After the victory dance (i.e. when the faster student is first to circle/highlight the phrase they hear), announce the next quadrant so that students know to listen for the next set of phrases, and begin reading where you left off. This avoids the pacing issue of students listening for many phrases on one large word cloud, and also gives a “reset” moment to the game.

Here’s a link to the a full size template. To use it, Make a Copy to your Drive, create 4 word clouds using Wordle.net (using Mozilla Firefox, NOT Chrome), save the word cloud files, then past them into each quadrant.