NYTimes Cooking recipes are so good, and they have these no-recipe recipes that both inspire you to experiment with what’s on hand, as well as remind you that yes, you can actually cook by combining ingredients you think would be good in a meal. You don’t actually need a recipe. Teaching isn’t really any different…

Continue readingTeaching with Compelling CI

Novellas: +2 Forward, -1 Back

With new novellas being published almost monthly at this point, opening up titles to choose from, I’ve been looking at how my own sequencing has been changing in the past year. I no longer feel the need to systematically read a) from lowest to highest word count, or b) shortest to longest book, a practice that constantly increases the demand of learners. If you think about it, what’s really the difference between that and using a highly sequenced textbook?! Such practice of constantly increasing demand also presumes learners have attended all classes, and/or develop language ability at the same rate, which is complete nonsense…

Continue readingMike Peto’s Read-Aloud

Get yourself over to the new COMPRHENDED! conference; it’s super cheap and flexible PD you can access until May. As a presenter, my main role is fielding any questions people have about what I presented, but I’ve also had time to poke around as a participant, too, and I’ve got a new activity for whole-class reading. Mike Peto of My Generation of Polyglots has been a champion of novels and independent reading for quite a while. He promotes having texts in your FVR (Free Voluntary Reading) library that students can read on their own, which means at-level, as well as below-level reading options, as supported by research on extensive reading (Jeon & Day, 2016). Still, there might be available texts that students need a bit of scaffolding to read. While most texts Latin teachers use are far above level, this whole-class reading strategy is worth sharing, especially for texts adapted to something closer to at-level (but probably still above-level). There’s also value in this reading approach with texts of all levels, especially in COVID times. I’ve used it with first year Latin students as recently as this week. It’s a robust reading process:

1) Teacher reads aloud as students listen

2) Reread paragraph-by-paragraph as students ask clarifying questions to help understanding (English is fine)

3) Reread again as students come up with comprehension questions that the teacher has to answer (English is fine)

Step #2 is an opportunity to establish meaning, but that doesn’t guarantee comprehension. The questions in step #3 are evidence that students understand…or not. For example, I was asked “where does she run to?” which is a fine question, only the text didn’t say that the character ran anywhere…yet. That gave me the opportunity to say “ohh, well she doesn’t run anywhere yet, but here we see that she wants to run to the stadium” as I pointed out the word vult. It could be a simple oversight, or the student might have a different mental picture of what’s going on in the story. In my experience, younger students will need coaching on how to ask a comprehension question. For example, I mentioned that “who, what, where, when, why, how?” were good question starters, but then I got a bunch of “why?” questions that couldn’t be answered from the text.

Zoom

Whereas my go-to reading strategy includes #1 as I help students process the meaning of Latin, steps #2 and #3 of Mike’s read-aloud promote a LOT more interaction. I like how the three steps are concrete tasks that keep the focus on Latin over Zoom. Other reading strategies rely on students holding themselves accountable for paying attention, and/or require the teacher to check comprehension. Over Zoom, that can get frustrating. With steps #2 and #3, it’s very obvious who needs more support (or who just isn’t there at the computer). Don’t make any judgements, either. I suspected a student had bailed, so while others were thinking of questions to ask, or sending me clarifying requests in direct messages—which I always replied to in general chat (e.g. “vult = she wants”)—I sent direct messages to the students I wasn’t certain were even there. Sure enough, they responded with something. This is the Zoom equivalent of the quiet student taking everything in.

100% Coverage ≠ 100% Comprehension

A question by a member of the Latin Best Practices FB group prompted me to look into text coverage, which ultimately led me to comprehension. These are two ideas that a lot of people have misinterpreted, much like the “4%er” figure, and even “90% target language use.” I’m thinking people have a hard time with mathematical concepts, and maybe we should avoid percentages moving forward. But first, we should take care of what damage has already been done by looking at simple examples right away:

Text Coverage

Text coverage is measured by tokens. There are five tokens in the sentence “the bird sees the cat.” Two of the tokens in that sentence happen to be the same word. Therefore, “the” represents 40% text coverage. If the reader doesn’t know “the,” they have a text coverage of 60%. The reader who knows everything except “cat” would have a text coverage of 80%.

Comprehension

Comprehension is a different idea entirely. If the reader who doesn’t know “cat” were asked “what does the bird see?” and it were scored, they’d have a comprehension score of zero. If they were asked two questions about the bird, and two questions about the cat, their score would be 50% comprehension with their 80% coverage of the text. Not the same thing.

Reading

Laufer et al.’s research shows that learners need a text coverage—not comprehension—of 98% ideally to read with ease (and 99-100% whenever possible), but that’s just getting through the reading. That 98% figure is just the start of comprehension.

Hold up.

Yeah, that’s right. Knowing 98% of a text—STOP!!—Remember the first section on tokens. It’s not 98 out of 100 different words, but 98 of 100 tokens (i.e. some words probably repeat). So, knowing 98% of a text doesn’t even guarantee comprehension of what is read. That’s quite the trip, isn’t it? It gets worse when we look at some findings from one of Eric Herman’s Acquisition Classroom Memos on exactly how [in]comprehensible reading can get with what seems like decent text coverage.

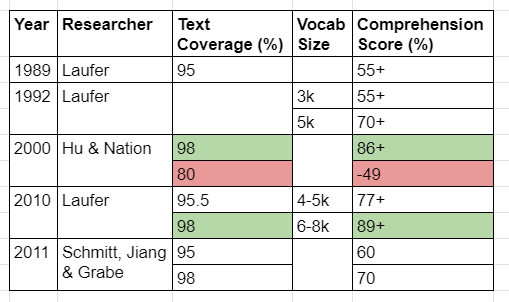

There’s a lot in that chart, but compare the text coverage to comprehension scores. Even 95% text coverage can get woefully low comprehension (55%). Keep in mind that the higher scores are still in the “most” range, as in learners are understanding most of what they read when they know 95%+ of a text. Also, those vocabulary sizes are incredibly high for what the majority of K-12 teachers should expect from their students. Eric also adds some context to the research:

“For the most part, the above reading studies were done with high proficiency students, ungraded and academic texts, and count word families. A reasonable prediction is that even higher text coverage and vocabulary size numbers are required to enable adequate comprehension of graded texts by lower level proficiency students. And this is not considering levels necessary for a confident and pleasurable reading experience, which would undoubtedly be even higher!“

Higher would be 100%. Let’s make sure we set the record straight:

- Students need to know 98% of a text to read it with ease.

- Reading with ease from knowing 98% of a text can still result in much lower comprehension scores, like 70%.

- Coverage ≠ comprehension

Providing students with texts of 98%…even 100% coverage of known words is step zero. It’s actually the minimum hope we could have for students reading with ease with high levels of comprehension. It turns out that text coverage isn’t very important to look at, because even knowing 100% of the words doesn’t guarantee 100% comprehension. It all goes back to vocab as top priority, sheltering whenever possible so gradual exposure to new words increases vocabulary without the burden of incomprehension. What does this mean for class? Probably using even fewer words than you think! Students can’t magically learn thousands of words, so if we expect them to comprehend high levels of what they read—especially during any kind of independent reading—we must use and create texts with a very limited number of words.

Circling & Scripts: Back To Them Roots (+ 59 Simple Story Starters)

Imma take a break from playing Root and get back to my teaching roots. Several recent experiences have reminded me that the most effective teaching practices are the basics, hands down. Obviously, COVID messed with us big time, but I’m afraid some of us have done a little too much adjusting that might result in lingering bad habits. Let’s face it, we pulled out all the stops on that beastly concert organ that was remote learning, and not all of what we did to make it happen could be considered even OK practices. We want good practices, and best ones whenever possible. Oh, and it’s been a while. Consider this: it will have been over two years since starting the school year with tried and true practices you’ve known to be effective. Yeah, that’s right. No one really did that in 2020, so it was August or September of 2019 when you last began the school year how you wanted. Will you remember what all those practices were? I’m not confident I will, so I’m writing this post to remind myself about them roots. Feel free to follow along…

Continue readingText Coverage & DCC’s Top 1000

**Updated 2.25.21 with details from this post**

The DCC frequency list is often consulted for choosing which words to use when writing Latin for students. It certainly makes sense to use ones they might encounter over and over again vs. those they might not, but *how* frequent are these frequent words? In particular, I was curious what a student could probably read having acquired the Top 1000 words on DCC’s list. Here’s some quick background…

Continue readingAgrippīna aurīga: Published!

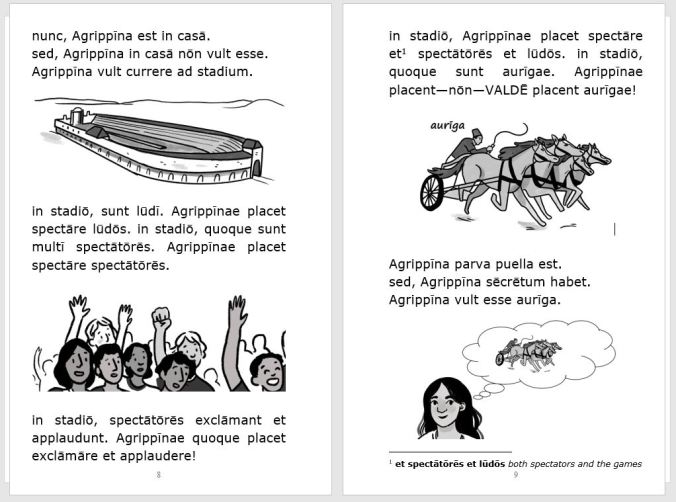

If you like Rūfus et arma ātra, you’ll love Agrippīna aurīga. This might very well be my most engaging text yet, at what I’ve come to see as the the rare “Goldilocks” intersection of comprehension, confidence, and compellingness.

Young Agrippina wants to race chariots, but a small girl from Lusitania couldn’t possibly do that…could she?! After a victorious race in the stadium of Emerita, the local crowd favorite charioteer, Gaius Appuleius Dicloes, runs into trouble, and it’s up to Agrippina to step into much bigger shoes. Can she take on the reins in this equine escapade?

24 cognates + 33 other words

1800 total length

We’ve known Piso’s family is from Hispānia all along. This book picks up on that with Agrippina, our strong mother, back in her childhood stomping grounds. I wanted to write a book with more action that could follow Rūfus et arma ātra. It turns out that I might want to read this before the sword-slinging saga. Agrippīna aurīga is written at a very similar level, though with 24 cognates compared to just two in Rūfus, and besides, I’ve realized that there’s no need to always increase the difficulty and length of each new book. In fact, that might be one way some kids get left in the dust. So, jumping “ahead” a little bit with this (aurīga) only to read a shorter book with fewer words (arma ātra) afterwards not only will go faster, but will also feel more confident a read for the students. Plus, it provides multiple opportunities to re-engage students who aren’t keeping up with reading on their own, and/or are missing far too many classes.

Michael Sintros (Duinneall), who worked with me on the creepy content of Quīntus et nox horrifica audiobook, once again has delivered engaging, ambient music with a new fantastic ancient instrument library. I cannot stress enough how crucial I’ve found these audiobooks to be towards making an unforgettable classroom experience. If I could combine the audio on Amazon as one purchase, I would, but you’ll have to get audio from Bandcamp to listen to with a physical book. Note that the eBooks from both Storylabs & Polyglots have audio included.

- For Sets, Packs, eBooks, and Audio—with reduced prices—order here

- Amazon

- eBooks: Storylabs & Polyglots (<– now includes audiobook!)

- Audiobook

- Free preview (through Chapter 5, no illustrations)

“…& Classical Humanities”

Almost every degree and teaching license I know of related to Latin attaches “& Classical Humanities” to the end. That is, it’s rare to study and teach the Latin language without also studying and teaching Classical Humanities.

Why is this?

I know, I know. They’re two peas in a pod. It might seem obvious since the culture most associated with Latin is Roman, part of the Classical era. Yet Latin has been around for thousands of years, right? Many cultures have used Latin, and not all of that Latin has been about the Romans, either. Consider teaching Classical Humanities without Latin. It’d be a history class focus on a particular time period, right? That’s like a history class on 18th century Spain. Now consider a high school Spanish language class. Surely, students don’t learn only about the18th century, much less Spain’s entire history, or even focus on just Spain at all! There are tons of Spanish-speaking cultures that have written about a ton of different stuff, and Spanish language classes take that into account.

Why not Latin?

Of course, the context of a Spanish class seems different, but is it, really? The Latin language didn’t die with the fall of the Roman Empire. In fact, non-Roman cultures have now been using Latin longer than the Romans existed. I’m not saying there are now more texts written by non-Romans than Romans. Then again…

TheLatinLibrary.com

The second I wrote that, I suddenly realized I had no idea whether it could be true. In what a colleague would say is very “on brand” of me, I ran some numbers through Voyant Tools, taking all ancient Latin texts from TheLatinLibrary, and comparing the total words to the Miscellany, Christian, Medieval, and Neo-Latin categories. It must be noted right away that this doesn’t represent all of the world’s extant Latin. In fact, I’m reading a work of elegiac couplets from the 15th century by Vincent Obsopoeus that’s nowhere to be found on TheLatinLibrary. There are thousands of words of Latin in there, but it won’t appear in my data. You won’t find works like Cornelia, or Ora Maritima, either. There’s no Hobbitus Ille in the data, and women are utterly underrepresented, with perhaps just Sulpicia and Egeria included in TheLatinLibrary at all. So, my source has its flaws, yet what we have of ancient Roman Latin is all there, or nearly all there, and these estimates* help put things into perspective. Of course, I went into this wondering if the world has surpassed the Romans in writing of Latin—prompting more inquiry into why the Classical Humanities are still a focus in high school Latin study—and the truth is undeniable, especially when acknowledging there’s so much recent Latin unaccounted for. Bottom, line, far more Latin has been written since the Romans than what you see here, which is already more than what we have from them:

A Solution To Asking Wrong Questions (e.g. “How Do You Teach X?”): Focus & Flip

Ask 10 teachers how they teach X, and you’ll probably get 10 different responses. However, if you flip it, and instead ask “how do students learn X?” you might get what in many cases is the only answer. Furthermore, it helps to focus the question first because most “how do you teach X?” questions are way too broad. Teachers can’t possibly teach everything about X, so there’s gotta be a more specific outcome to the question. What is the point of X? Or, what are students expected to do, or know about X? For example…

- Take a question teachers always ask:

- How do you teach the subjunctive?

- Focus it:

- How do you teach students to identify subjunctive verb forms?

- Flip It:

- How do students learn to identify subjunctive verb forms?

In this case, the answer is quite simple: students must memorize verb forms. There’s no way around that one. Humans won’t spontaneously infer which verbs are subjunctive. To identify them, students will have to be shown what they are, commit them to memory, and then recall from memory. So, the teacher who expects students to identify subjunctive verb forms needs to provide them, and hope their students have good memories (oh right, that last part is out of their control). Not a very reliable thing to expect, it turns out.

Consider back to the alternative, too. Just think of all the different answers you could get to “how do you teach the subjunctive?” They’ll probably all be from the teacher’s perspective, like descriptions of activities, and have nothing to do with the actual learning that must go on, too. This is probably why so many teachers reinvent the wheel year after year. The teaching isn’t actually addressing what students need to learn. Of course, that grammar question is a bit silly since the focus doesn’t have much use. Let’s look at a related question with a more useful purpose…

- Q: How do you get students using the subjunctive?

- Focus: How do you get students to speak using accurate subjunctive verb forms?

- Flip: How do students learn to accurately speak using subjunctive verb forms?

This answer is also simple: time & exposure. Accuracy, especially in speaking, isn’t expected for the first years (3-4+), with or without any “error” correction, either. For any language to come out (output), students need lots of examples coming in (input). So, the teacher who expects accurate use of subjunctive, then, needs to ensure that there are tons of examples of subjunctive verb forms in what students listen to and read. Oh, and they also need to have patience. Any teacher who expects—and gets—beginner students speaking accurate subjunctive verb forms either doesn’t know the research, measures that in isolation and moves on, or is seeing short term memory results. Yet also probably holds “review” sessions each year!

So, give Focus & Flip a try!

Love Stories

Wait…next week is Valentine’s Day already?! Crazy. Also, it’s kind of a terrible holiday, though isn’t it? My best memories are of the perforated cards you’d exchange in elementary school just hoping one kid had cool enough parents to buy them the Valentines that had Thundercats or GI Joe characters being all lovey on them. Never liked the heart candy; those were just awful. Anyway, if you have the following books on hand, consider reading them to students this week, or scoop up one of the new eBooks so students can read on their own. Here are novellas that contain stories about the joys of relationships, as well as their challenges:

Sitne amor? (Amazon, eBook Polyglots, eBook on Storylabs)

For first year Latin students, there’s the LGBTQ-friendly book of 2400 words about desire, and discovery, in which Piso crashes and burns when he’s around Syra.

Pluto: fabula amoris (Amazon)

For first or second year Latin students looking for a quick read in a book of 1070 words, there’s this take on the Pluto & Proserpina myth.

Pandora (Amazon, eBook Polyglots, eBook on Storylabs)

For first year Latin students looking for a longer novella of 4200 total words, there’s the adaptation of the Pandora myth.

Ovidius Mus (Amazon)

The three stories based on Ovid in this book 1075 words are designed for readers at the end of their first year.

Unguentum (Amazon)

This book of 1575 words is an adaptation of Catullus 13, and includes tiered versions of the original.

Euryidice: fabula amoris (Amazon)

This book, much like its prequel Pluto, includes a different take on the Eurydice & Orpheus myth.

Medea et Peregrinus Pulcherrimus (Amazon)

A Latin III book of 7500 words in this adaptation of the Golden Fleece.

Carmen Megilli (Amazon)

A Latin III book of 9300 words in this that includes an LGBTQ-friendly love story.

Cupid et Psyche (Amazon)

A Latin III/IV book of 8800 words in this adaptation of of Apuleius.

Ira Veneris (Amazon)

A Latin III/IV book of 11000 words in this follow-up to Cupid & Psyche.