In cobbling together sources for my 2025 MTA Summer Conference presentation on “Getting More from Your Formative Assessments and Grading,” I searched my blog to link posts on books I consider foundational. Somehow, I never published the post I wrote after reading Zerwin’s “Point-less” years back. Her work deserves some attention…

Continue readingAssessment & Grading & MGMT

Achieving Consensus: A Key To Changing Teacher Practice

If I were ever asked to coordinate a schoolwide grading system change again, I would take a cue from the authors of Data Wise: A Step-by-Step Guide to Using Assessment Results to Improve Teaching and Learning (2013). In Chapter 6, this gem of a statement reads…

Continue reading“It is easy to achieve consensus on solutions that do not require teachers to make changes in their day-to-day practice, even when data show that such practices are consistently ineffective.” (pp. 140-141)

Current Reading: An Awesome Trilogy – Starch & Elliot Studies From 1912-13 Showing The Ridiculous Unreliability of Grading

I love the studies carried out over 110 years ago by Starch & Elliott (1912, 1913a, 1913b). In short, they tested the reliability of English teachers grading papers (1912), and got disastrous results showing an absurd amount of variation in scores across many teachers. Then, they did a second study with geometry teachers (1913), got even greater variation of scores, and finally did a third study with history teachers, essentially replicating the results from the other two.

I often cite these when talking shop, saying something like “we’ve known for 100 years that grading can be incredibly unreliable,” but recently I revisited these foundational studies, and now have an even greater appreciation for their design and findings. In this blog post, I’ll dig into these groundbreaking studies, starting with the 1912 edition…

Continue readingFalse Formatives

Click here for the updated model and latest research.

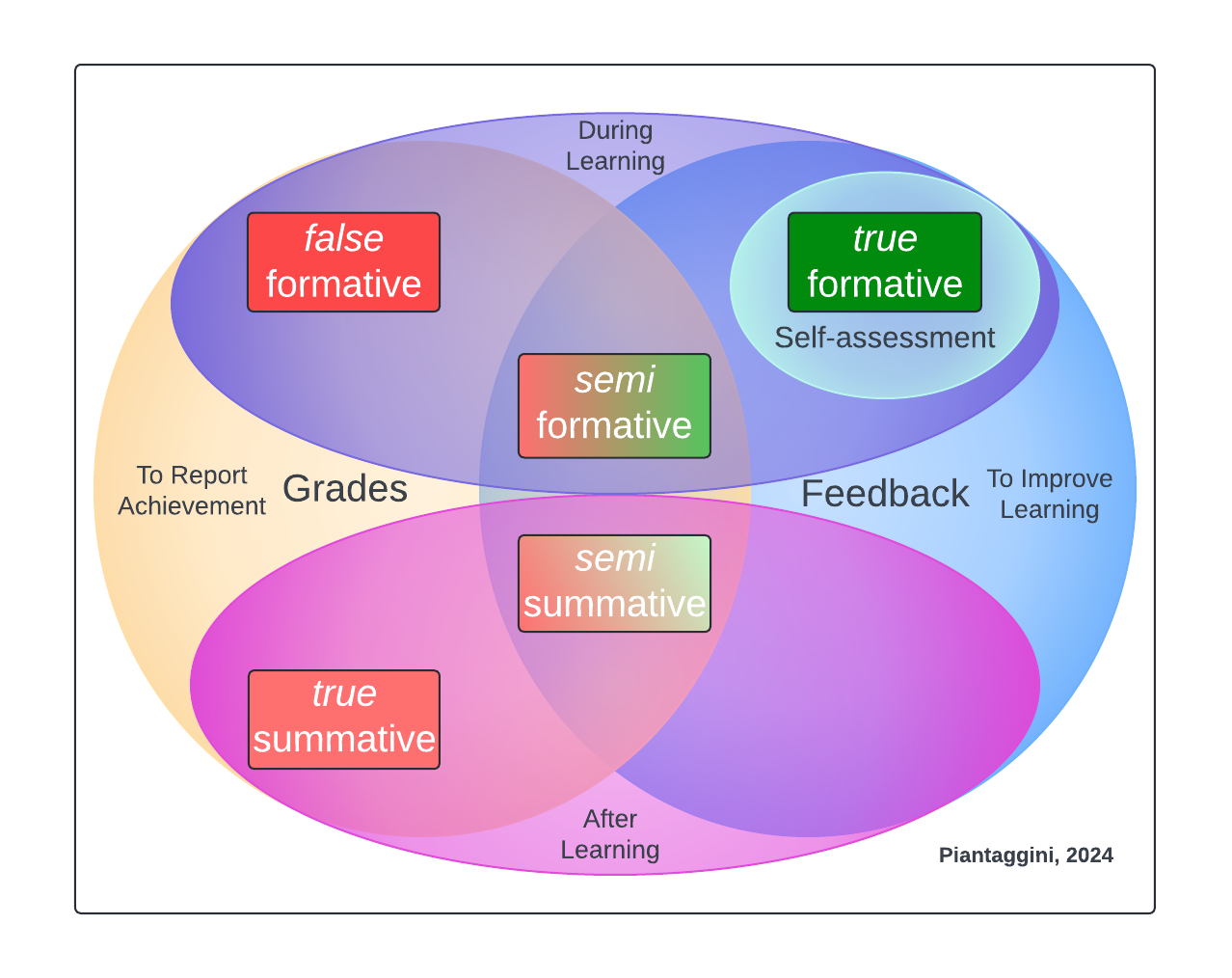

I just presented a poster session in Chicago for the NCME Special Conference on Classroom Assessment (Piantaggini, 2024). While I had some rough details for a proposed dissertation study, the focus of discussion with scholars who stopped by was my new assessment model and the theoretical framework that brought me to it. The message I got was “I think you’re onto something,” so I’m sharing my work here to get more eyes on it. Please contact me with any embarrassingly scathing criticism. Otherwise, reply publicly with any other thoughts or questions. After all, this is my blog, not peer review!

So, in this blog post, I’ll describe the model you see above, and how I got there, starting with a major dilemma I identified when reviewing literature on classroom assessment: confusion over grading formative assessments…

Continue readingCurrent Reading: Flexible Deadlines ≠ “No Deadlines” (i.e., Extensions vs. Reassessing)

One concern with flexible deadlines is that in the absence of late work penalties, students will wait until the absolute last, last, last, last, LAST possible moment to turn in their assignments. The fear is that this will create a ton of extra work for the teacher, and that students will not develop time management skills since there are no consequences of a lower grade/reduced points)…because all students in traditional points-based grading systems turn in ALL of their assignments on time, right? And then they graduate and become college students who continue to turn in ALL of their assignments on time, right? And then they graduate and become employees who complete ALL of their tasks on time while being adults who get done ALL of their errands on time, right? All because of low grades and reduced points in school…right? This belief has prevailed despite the lack of empirical evidence to support it. Granted, the fear does seem to play out in some cases when flexible deadlines are misused, or there is some other assessment policy getting in the way. Nonetheless, for any change to take place, this belief must be addressed…

Continue readingCurrent Reading: Assessing Students Not Standards (Jung, 2024)

Given over 20 years of schools attempting to implement standards-based grading (SBG), Lee Ann Jung’s 2024 release, Assessing Students Not Standards, offers a refreshing alternative. Is it part of a post-SBG era? Maybe. There are a lot of SBG concepts that are universally good, and the message is clear from researchers and teachers: let’s keep those. But there’s more. We can rebuild SBG. We have the experience. We can make SBG better than it was. Better, stronger, faster.

Another message is getting clearer, too, and seems right at home with the ungrading movement. Jung states “we need to grade better, but we also need to grade less. A lot less” (p. 20). This is aligned with my own research on exploring 1) ways to reduce summative grading, and 2) find formative grading alternatives (i.e., so they remain formative). So, let’s get into some stuff in the book…

Continue readingCurrent Reading: Grades Discourage Students Seeking A Challenge

Susan Harter was interested in the effects of extrinsic rewards on children. In 1978, she found that grades influenced whether students chose to complete tasks at a higher difficulty. In this study, 6th graders were assigned to a “game” group, or “grade” group and were asked to solve 8 anagram puzzles. The children in the game group were told to choose one of four difficulty levels. Those in the grade group were given the additional instructions that they would be graded on the number of correctly-solved anagrams (i.e., 8 = A, 6 = B, 4 = C, 2 = D, and 0 = F).

Unsurprisingly, the game group (i.e., ungraded) chose the more-challenging tasks, while the grades group chose the less-challenging tasks. Surprisingly, when children were asked which tasks they might have chosen if they were in the other group, the responses matched. That is, the game group said that if they were in the grades group they would have chosen easier tasks, and the grades group said that if they were in the game group they would have chosen harder tasks. In other words, each group confirmed that being graded discourages taking risks.

As if the negative association of grades on learning weren’t clear enough from those findings alone, Harter also recorded the children…smiling! Yes, smiling. It turns out that children in the games group smiled more after solving each puzzle than children in the grades group.

This all makes sense.

In talking to various stakeholders, high-achieving students are overly concerned with their GPA. They will do anything to maintain it, which includes opting for classes that get an “easy A.” Sadly, these students are often stressed out, motivated by high-stakes rewards, and tend to enjoy themselves less. They don’t do much smiling, and tend to be unhappy with their academics. On the other end, struggling students aren’t motivated by grades at all! For them, these rewards are actually punishments (i.e., low grade, after low grade, after low grade). They hardly smile, and tend to be unhappy because there’s often very little hope for improving, especially in grading systems with zeros and averaging low scores into the course grade!

Families are another important stakeholder group. They often view grades as a motivator that gets their students working hard, and striving to do better. But do they know grades are likely keeping their star-student from going above and beyond? I wonder what they would think about Harter’s findings. After all, it’s almost impossible to know that grades are negatively impacting students from the surface. That is, when the focus is on achievement, the process of how students get there tends to be ignored. High grades might give family members the sense that their student is being challenged, but are they? Who’s to say they aren’t doing just enough to get those high grades, and nothing more once they’re achieved? Who’s to say they’re actually taking the kind of intellectual risks their families want? And are they even enjoying learning? Harter’s study suggests otherwise.

To summarize Harter’s findings, grades discouraged children from taking risks, and children had less fun solving puzzles because of grades. This is just one more study showing how grades get in the way of learning. Furthermore, Harter’s findings support my work in searching for ways to 1) reduce summative grading (i.e., grade fewer assessments, less often), and 2) use formative grading alternatives (i.e., use practices that allow formatives to remain ungraded).

Reference

Harter, S. (1978). Pleasure Derived from Challenge and the Effects of Receiving Grades on Children’s Difficulty Level Choices. Child Development, 49(3), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128249

Multi-day Assessments

I now get to see a decent amount of teaching by pre-service students, as well as current teachers in the field—something every educator would benefit from, yet is almost never built into teaching schedules, sadly. One thing I overheard last fall was something like “after writing your conclusion, be sure to submit your lab; I’ll be reviewing these over the weekend,” and then the class began a brand new unit.

It occurred to me that the teacher wasn’t going to finish reviewing students’ work for days—outside of contractual hours, no less—which means the teacher wasn’t going to discover any struggling individuals (or groups) until long after anything could be done, like the two boys I saw in the back of the room who had fairly blank lab reports. In other words, this isn’t an example of timely feedback that would have otherwise improve learning, which affects both teacher and student.

In this particular case, when the teacher found out that a certain number of students didn’t understand Unit 1 content, what was the plan? Pause the current Unit 2, then go back?! Why did they go on to Unit 2 in the first place?! I found myself wondering: “what could be done with the lab report to avoid all this? How might we break up the assignment so that all the feedback is timely, and there’s no moving forward only to fall back?” Let’s take a cue from some graduate work…

Continue readingCurrent Reading: Zeros = -6.0!!!!

**Updated 4.6.24 w/ quantitative results on minimum 50 grading**

We know that the 100-point scale has a staggering 60 points that fall within the F range, then just 10 points for each letter grade above. This major imbalance means that averaging zeros into a student’s course grade often has disastrous results, and can become mission insurmountable for getting out of that rut.

Still, the argument against zeros is surprisingly still going on, with advocates in plenty of schools everywhere claiming the old “something for nothing myth” when alternatives are suggest, like setting the lowest grade possible as a 50 (i.e., “minimum 50). In other words, teachers are still unconvinced that they need to stop using zeros. Well, we’re heading back 20 years to when Doug Reeves (2004) used a 4.0 grading scale example to show exactly how utterly absurd and destructive zeros are in practice. This is perhaps the most compelling mathematical case against the zero I’ve come across yet….

Continue readingCurrent Reading: Retakes—When They Do And Don’t Make Sense

My recent review of assessment has continued, which now includes two major findings:

- Grading is a summative function (i.e., formative assessments should not be graded).

(Black et al., 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Bloom, 1968; Boston, 2002; Brookhart, 2004; Chen & Bonner, 2017; Dixson & Worrell, 2016; Frisbie & Waltman, 1992; Koenka & Anderman, 2019; Hughes, 2011; O’Connor et al., 2018; O’Connor & Wormeli, 2011; Peters & Buckmiller, 2014; Reedy, 1995; Sadler, 1989; Shepard et al., 2018; Shepard, 2019; Townsley, 2022) - Findings from an overwhelming number of researchers spanning 120 years suggest that grades hinder learning (re: reliability issues, ineffectiveness compared to feedback, or other negative associations).

(Black et al., 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Brimi, 2011; Brookhart et al, 2016; Butler & Nisan, 1986; Butler, 1987; Cardelle & Corno, 1981; Cizek et al., 1996; Crooks, 1933; Crooks, 1988; Dewey, 1903; Elawar & Corno, 1985; Ferguson, 2013; Guberman, 2021; Harlen, 2005; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Johnson, 1911; Koenka et al., 2021; Koenka, 2022; Kohn, 2011; Lichty, & Retallick, 2017; Mandouit & Hattie, 2023; McLaughlin, 1992; Meyer, 1908; Newton et al., 2020; O’Connor et al., 2018; Page, 1958; Rugg, 1918; Peters & Buckmiller, 2014; Shepard et al., 2018; Shepard, 2019; Starch, 1913; Steward & White, 1976; Stiggins, 1994; Tannock, 2015; Wisniewski et al., 2020)

In other words, 1) any assessment that a teacher grades automatically becomes summative, even if they call it “formative” (I’m referring to these as false formatives), and perhaps more importantly, 2) grades get in the way of learning. These findings suggest that best way to support learning is by a) limiting grading to only true summative assessments given at the end of the grading period (e.g., quarter, trimester, semester, academic year), and b) using alternatives to grading formative assessments that otherwise effectively make them summative. Therefore, my next stage of reviewing literature focuses on reducing summative grading and exploring formative grading alternatives (i.e., so they remain formative). As for now, one of those practices *might* be retakes, which has been on my mind ever since I saw a tweet from @JoeFeldman. Given the findings above, which establish a theoretical framework to study grading, let’s take a look at how retakes are used now, and how they could be used in the future, if we even need them at all…

Continue reading