Click here for the updated model and latest research.

I just presented a poster session in Chicago for the NCME Special Conference on Classroom Assessment (Piantaggini, 2024). While I had some rough details for a proposed dissertation study, the focus of discussion with scholars who stopped by was my new assessment model and the theoretical framework that brought me to it. The message I got was “I think you’re onto something,” so I’m sharing my work here to get more eyes on it. Please contact me with any embarrassingly scathing criticism. Otherwise, reply publicly with any other thoughts or questions. After all, this is my blog, not peer review!

So, in this blog post, I’ll describe the model you see above, and how I got there, starting with a major dilemma I identified when reviewing literature on classroom assessment: confusion over grading formative assessments…

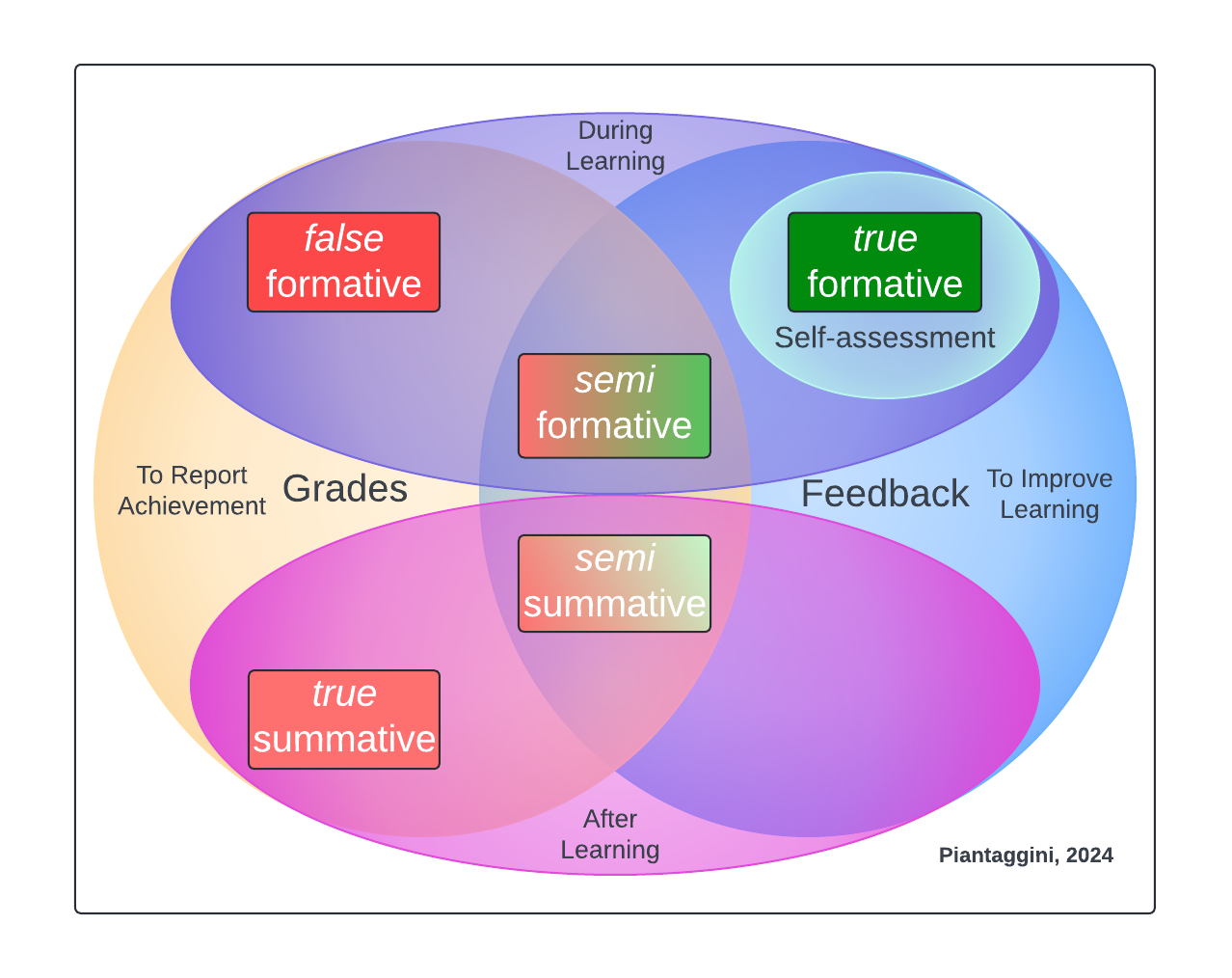

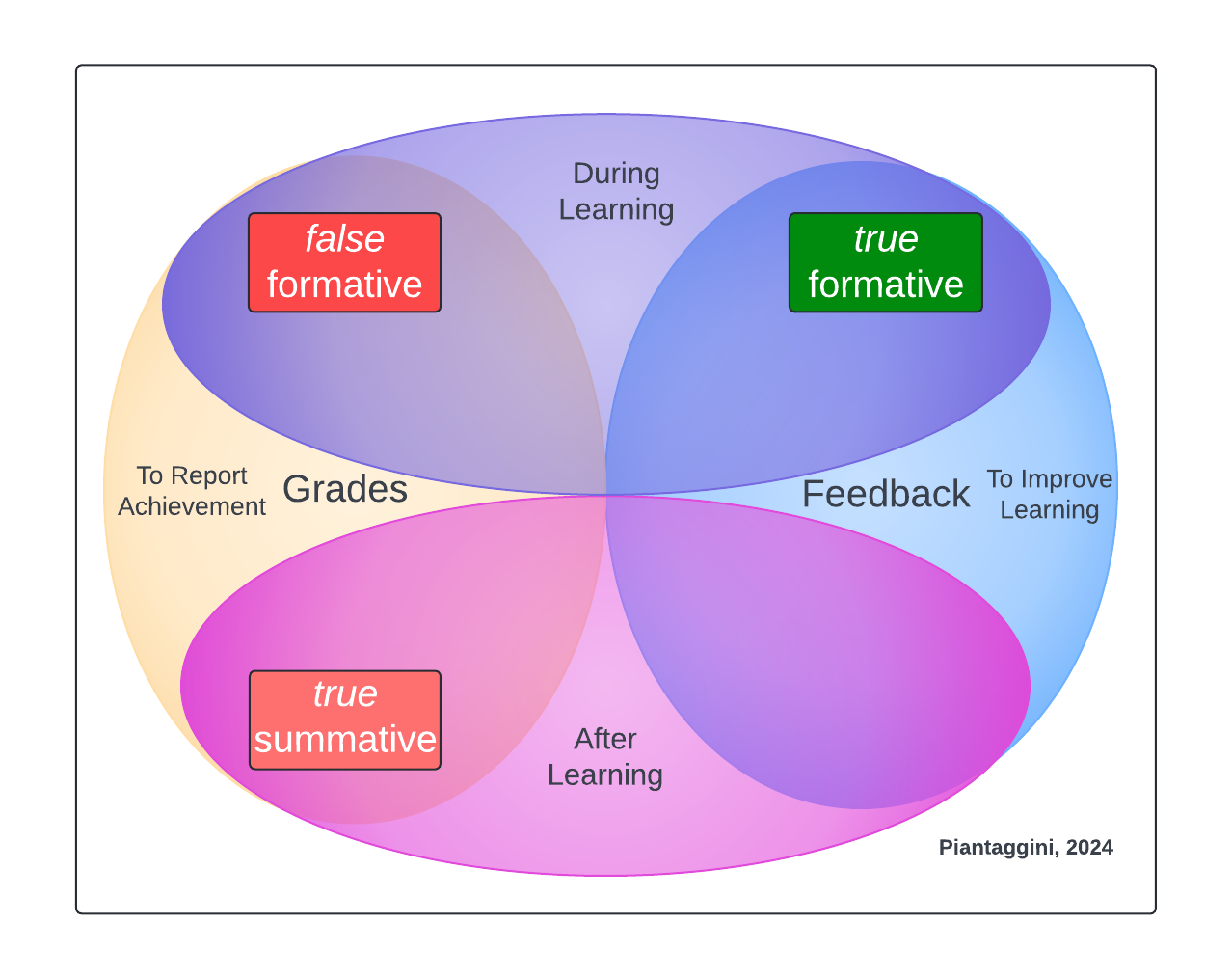

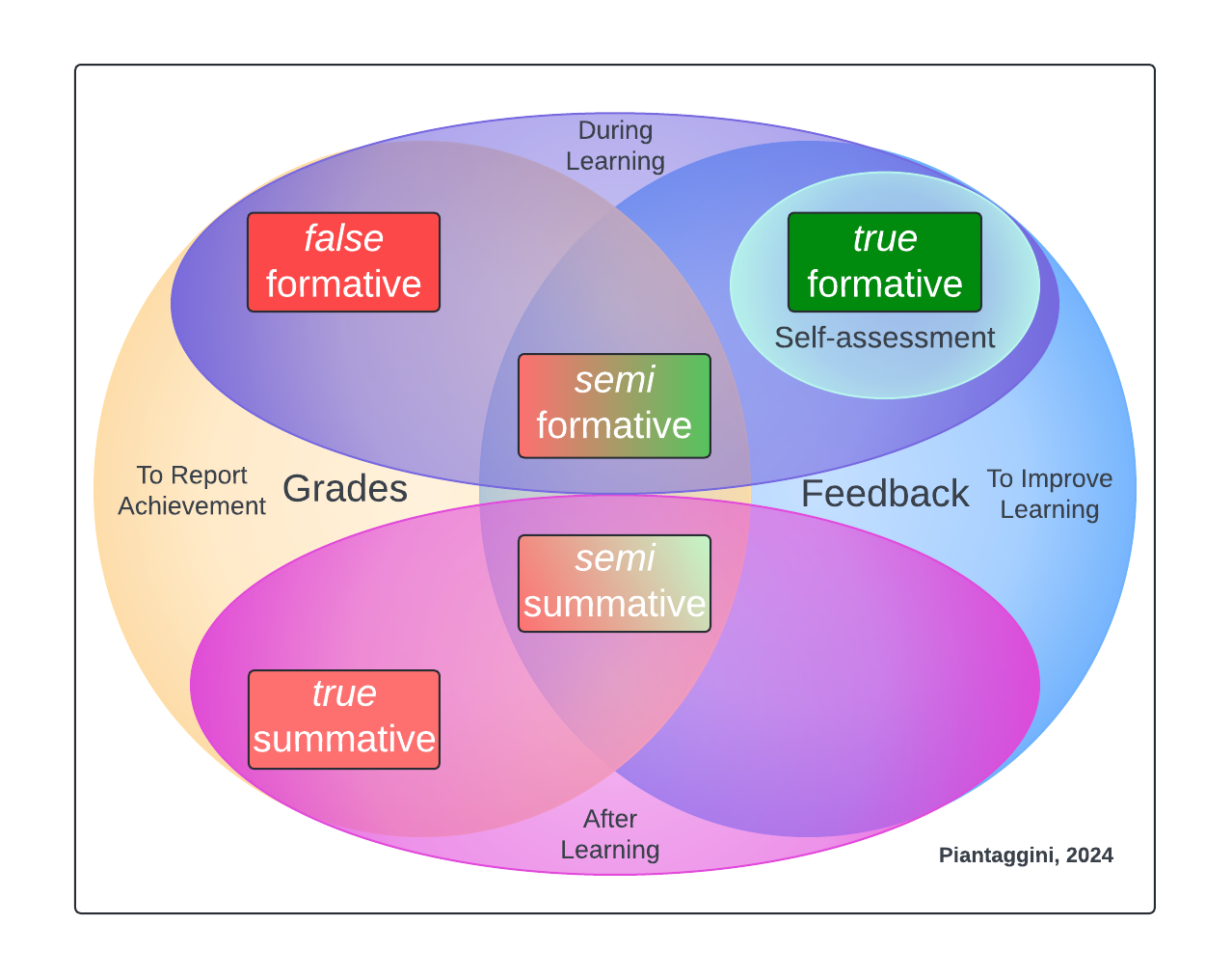

To understand this dilemma, here’s a Venn diagram of the two basic types of classroom assessment and their qualities:

This is showing that formative assessments are used to improve student learning while it is taking place, and summative assessments are used to report achievement after learning has taken place. While providing feedback is formative, grading is summative (Black et al., 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Bloom, 1968; Boston, 2002; Brookhart, 2004; Chen & Bonner, 2017; Dixson & Worrell, 2016; Frisbie & Waltman, 1992; Koenka & Anderman, 2019; Guskey & Link, 2019; Hughes, 2011; O’Connor et al., 2018; Peters & Buckmiller, 2014; Reedy, 1995; Sadler, 1989; Shepard et al., 2018; Shepard, 2019; Townsley, 2022).

In practice, however, these two different ways of assessing that should be serving two different functions end up becoming fused and confused (Duschl & Gitomer, 1997; Guskey, 2019; Lichty, & Retallick, 2017; McMillan, 2001; Morris & McKenzie, 2023; Siegel & Wissehr, 2011). That is, instead of reporting achievement after learning occurs, graded formatives mean achievement is being reporting while learning is taking place. When these grades count towards a course grade/GPA, they distort actual achievement, especially when averaging old, lower scores, with newer, higher ones. Even if by chance those grades are not averaged, we still have a situation where a student is being told what their achievement level is—sometimes daily—when they should be focusing on how to improve.

Since grading formatives changes the function from improving learning to reporting achievement, anything called “formative” effectively becomes summative by definition. This bypasses the formative feedback process students need. Townsley (2022) commented on this confusion, stating “some educators may believe that formative assessment is a smaller summative assessment rather than a process” (p. 49). Recent evidence I’ve collected from teachers supports this as well, suggesting that they consider “formative” to mean assessments that are small in scope and frequently given, and “summative” to mean they are big in scope and occur far less often. Unfortunately, there is hardly enough time to provide much feedback when formatives confused as summatives. Therefore, when frequently occurring assessments are graded and lack feedback, we get what I’m calling “false formatives.” The updated Venn diagram below reflects how formatives and summatives should be used, or what I’m calling “true,” alongside those graded formatives that lack feedback, or what I’m calling “false.”

Before continuing, I must point out that these terms are supposed to provoke. We do have a dilemma, after all, and there is value in treating the matter with at least some sense of urgency rather than softening it (conf. “climate crisis” vs. “climate change” rhetoric). No, you’re not a bad teacher for doing something that no one’s been talking about. This just needs to be part of the assessment and grading conversation moving forward. Again, these terms are intended to signal “hmm, I thought I was doing one thing (i.e., true), but it turns out I’m not (i.e., false).” In the case of false formatives, that would sound like “hmm, I thought I was assessing to improve learning, but it turns out I’m reporting achievement instead.” In other words, practice is straying from its intended use, and this one has significant implications.

The significant implications are such that this is not just a definition dilemma, or a theoretical exercise. O’Connor & Wormeli (2011) offer a strong case summarizing the consensus of why we would want to grade only summatives (and not formatives), stating “if we grade the formative steps that students take as they wrestle with new learning, every formative assessment becomes a final judgment, with no chance for revision and improvement. Feedback is diminished, and learning wanes (pp. 43-44).” In fact, my review of the literature has uncovered over 40 studies spanning 120 years from Dewey (1903) to Mandouit & Hattie (2023) suggesting that grades hinder learning, and I’m nowhere near finished with that review! In sum, grading is not something we want to be doing much of at all, and when formatives are frequently graded we’re in the danger zone, especially if there’s no feedback. But what kind of feedback is effective for improving learning? Not all of it.

Providing useful feedback is the defining characteristic of formative assessment. That is, something like “good job!” does not count as useful information to improve learning. Sadler (1989) identified three conditions necessary for feedback to be useful: students need feedback that helps them (a) understand expectations, (b) recognize any gaps, and (c) do something that closes gaps, getting them closer to the original expectations. Involving students in the feedback process through self-assessment is also a major component of formative assessment (Black et al., 2004; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Boston, 2002; Darrow et al., 2002; DeLuca et al., 2023; Falchikov & Boud, 1989; Falchikov & Goldfinch, 2000; Stiggins, 1994; White & Frederiksen, 1998). That is, one-way comments do not satisfy Sadler’s feedback conditions, even if those comments contain actionable information. Students must be involved. Therefore, the teacher needs to allow students to do the thinking on their own, as least in (a) understanding expectations, and (b) recognizing any gaps. Then, the teacher’s role can be more prominent in suggesting ways that the student could satisfy the third condition, (c) doing something that closes gaps. The updated Venn diagram below shows how providing feedback must involve students through self-assessment.

Aside from false formatives, there are other combinations of formative and summative qualities that serve conflicting purposes that I’m calling “semis.” For example, formatives that do have feedback but also grades are what I call semi formatives, and summatives that have extra feedback are what I call semi summatives. The latter is an interesting category, though not uncommon, because the student can’t do anything about the feedback they get if they also have been given a summative grade reporting their achievement. For example, an end-of-term paper with comments leaves the student unable to revise. If there is some kind of revision policy for the purpose of improving student performance (and not just to get a higher grade), then one wonders why a grade was given in the first place. n.b. More often than not, grades are assigned due to actual, or perceived policies (not sound assessment principles). I encourage educators to find out how necessary grades are, and when. You might be surprised that certain grading “requirements” presenting themselves as the “grammar of schooling” (Tyack & Cuban, 1997) are more like guidelines, really, and have far more wiggle room, allowing for more effective assessment. While semi formatives and summatives both have feedback, the power of that feedback to improve learning is reduced by grading. The colors in the full Venn diagram below represent a continuum from hindering to improving learning, with red representing assessments that hinder learning, and green representing assessments that improve it.

Note that false formatives—shaded darkest red—are to be avoided at all costs due to their lack of feedback, use of grades, and their higher frequency that occurs all throughout the learning process. It is also important to recognize that the formative qualities of semi formatives and summatives do not make them worthwhile alternatives to true formatives. That is, adding feedback to a true summative does not change the function from reporting learning to improving learning. This is because grades have a certain force, and the benefits of feedback are unlikely to negate that force. As Shepard et al. (2018) put it, grading “more than any other single factor tends to undermine the good intentions of formative assessment” (p. 29). Based on the theoretical framework and my new model, we want to spend as much time possible in the upper right quadrant of true formatives, which means not grading assessments and providing feedback that involves students through self-assessment.

Sidebar

One conversation I had with a Chicago Reading Specialist, Leslie Russell, illustrated some challenges with the model. You’ll notice that there’s nothing in the lower right hand corner. This was intentional on my part, but Leslie wondered about the times when she’s (a) given students a non-graded summative reading assessment at the end of the school year (b) while also providing feedback on what to do over the summer, thus increasing their learning next fall (as evident by diagnostic tests). This example appears to have summative and formative qualities that would put it in that lower right hand corner, and I appreciate how long Leslie stayed at my poster as we talked through ideas, struggling to resolve why I didn’t think anything should be there. I knew there shouldn’t, but I couldn’t articulate it at the time.

Late that night, however, I sprung from lucid sleep with a thought. One thing we might have overlooked in the conversation is that the entire model rests on assessing learning, which we must presume to be some objective, or standard. I see two possibilities in Leslie’s example. First, the student did not meet their standard/objective, and was given feedback on how to improve. Despite this occurring at the end of the school year, the student would still be in the learning phase based on their own learning rate (not the school calendar). The diagnostic showed improved learning, so we could conclude that the feedback satisfied Sadler’s (1989) feedback conditions. Since no grade was given, this could be an example of a true formative, just with the summer right in the middle. The second possibility is that the student met their reading standard/objective for the year, and then the feedback Leslie gave was actually on the next standard/objective. I would argue that both cases are still examples of true formatives, and that the end-of-school year timeline was being confused with the end-of-student-learning quality of summatives, which is not bound by the academic calendar.

Still, I told Leslie I was going to think through what that missing corner could look like and I did just that on the train ride back to MA. So, at least theoretically, we could consider an assessment given after a student has met a standard/objective with feedback specific to the next stage of learning as a type of summative I’m calling a “forward summative.” In practice, it would be the same as starting a new learning and feedback cycle on a new standard/objective, but there might be something valuable in the idea of extending learning, perhaps when combined with learning progressions (Jung, 2024). For example, when a student reaches the end of one learning progression rubric (e.g., the 4th stage of 16 stages), the assessment could be considered a forward summative. The most important quality in this thought experiment is the one that’s absent: grades. For the sake of theory, then, I present an updated Venn diagram that could complete this model if one were to explore that idea of forward summatives, and I give thanks to Leslie for the conversation that spurred it.

Where to Next?

While findings from a pilot study I conducted cannot be generalizable beyond a small urban public high school in New England (Piantaggini, 2023), I did find that self-assessment was not used much at that particular school, based on three student interviews and information contained in 30 teacher syllabi. Students might have been getting comments, but they were not involved in a back-and-forth dialogue with their teachers about (a) understand expectations, (b) recognize any gaps, and (c) do something that closes gaps (Sadler, 1989). In other words, there was not much evidence of students getting feedback that improves learning. Additional information from teacher syllabi on their assessment and grading practices suggests it is possible that false formatives were widely prevalent, at least in that one school. In other words, student learning might have been hindered by grading formatives. The dilemma might have found its way to that school.

But looking into the extent to which false formatives were prevalent at the school was not the purpose of that study. This is something I’m interested in studying in the future, investigating whether students receive useful feedback, especially if false formatives are prevalent in their school. One research question I have is whether other related assessment and grading practices mitigate the negative effects of false formatives. For example, does having students self-assess, and retake assessments improve learning, despite students seeing grades and not having initial feedback? We’ll see.

In the meantime, all available signs point to avoiding false formatives whenever possible, which can be tricky if you’re in a school with one of those “two grades in the gradebook per week” policies. My best advice is to report student work as being collected only (i.e., no grade), and then make sure whatever feedback you give is connected to that assignment (e.g., a direct link to something else, or copy/pasted into the assignment comment field). This should satisfy the “how’s my kid doing?” and “how can they improve?” questions that come up as long as you can point to specific, actionable feedback being given. In my experience, all you need is one grade during the first progress report (i.e., halfway point of the grading term). With this one grade in there stakeholders are satisfied whenever they check the gradebook (vs. seeing a blank one, or seeing learning evidence without a grade). Then, you can report a grade just once per grading term after that as long as there’s that trail of learning evidence everyone’s looking for. After all, the real reason behind those arbitrary “two grades per week” policies is students and families being unsure of their achievement, most likely due to grading piling up and teachers not having adequate time to keep the gradebook current. Therefore, I encourage you to explore those policies, and think of them more as maintaining a current gradebook with information and symbols, just not grades until they’re absolutely necessary at the end of the grading term.

References

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the Black Box: Assessment for Learning in the Classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 86(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170408600105

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Bloom, B. S. (1968). Learning for Mastery. Instruction and Curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, Topical Papers and Reprints, Number 1. Evaluation Comment, 1(2), 1–12.

Boston, C. (2002). The Concept of Formative Assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 8(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7275/kmcq-dj31

Boud, D. (1989). THE ROLE OF SELF‐ASSESSMENT IN STUDENT GRADING. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 14(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293890140103

Brookhart, S. M. (2004). Assessment theory for college classrooms. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2004(100), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.165

Chen, P. P., & Bonner, S. M. (2017). Teachers’ Beliefs about Grading Practices and a Constructivist Approach to Teaching. Educational Assessment, 22(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2016.1271703

DeLuca, C., Willis, J., Dorji, K., & Sherman, A. (2023). Cultivating reflective teachers: Challenging power and promoting pedagogy of self-assessment in Australian, Bhutanese, and Canadian teacher education programs. Power and Education, 15(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/17577438221108240

Dewey, J. (1903). Ethical Principles Underlying Education. The University of Chicago Press.

Dixson, D. D., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Formative and Summative Assessment in the Classroom. Theory Into Practice, 55(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148989

Duschl, R. A., & Gitomer, D. H. (1997). Strategies and Challenges to Changing the Focus of Assessment and Instruction in Science Classrooms. Educational Assessment, 4(1), 37–73. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326977ea0401_2

Falchikov, N., & Boud, D. (1989). Student Self-Assessment in Higher Education: A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research, 59(4), 395–430. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170205

Falchikov, N., & Goldfinch, J. (2000). Student peer assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis comparing peer and teacher marks. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 287–322. https://www.proquest.com/docview/214115677/abstract/4035ABE5C20E4321PQ/1

Frisbie, D. A., & Waltman, K. K. (1992). Developing a Personal Grading Plan. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 11(3), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1992.tb00251.x

Guskey, T. R. (2019). Grades versus comments: Research on student feedback. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(3), 42–47.

Guskey, T. R., & Link, L. J. (2019). Exploring the factors teachers consider in determining students’ grades. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 26(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2018.1555515

Hughes, G. (2011). Towards a personal best: a case for introducing ipsative assessment in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 36(3), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.486859

Jung, L. A. (2024). Assessing Students, Not Standards: Begin With What Matters Most (1st edition). Corwin.

Koenka, A. C., & Anderman, E. M. (2019). Personalized feedback as a strategy for improving motivation and performance among middle school students. Middle School Journal, 50(5), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2019.1674768

Lichty, J., & Retallick, M. (2017). Iowa Agricultural Educators’ Current and Perceived Grading Practices. Journal of Research in Technical Careers, 1(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.9741/2578-2118.1000

Mandouit, L., & Hattie, J. (2023). Revisiting “The Power of Feedback” from the perspective of the learner. Learning and Instruction, 84, 101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101718

McMillan, J. H. (2001). Secondary Teachers’ Classroom Assessment and Grading Practices. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 20(1), 20–32.

Morris, S., & McKenzie, S. (2023). A Glimpse into Arkansas Teachers’ Grading Practices. Education Reform Faculty and Graduate Students Publications. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/edrepub/144

O’Connor, K., & Wormeli, R. (2011). Reporting student learning. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 40.

O’Connor, K., Jung, L., & Reeves, D. (2018). Gearing up for FAST grading and reporting. Phi Delta Kappan, 99, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718775683

Peters, R. E., & Buckmiller, T. (2014). Our Grades Were Broken: Overcoming Barriers and Challenges to Implementing Standards-Based Grading. Journal of Educational Leadership in Action, 2(2). https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/ela/vol2/iss2/2

Piantaggini, L., (2023, May 18). Learning For Yourself, Not For The Teachers [Poster session], University of Massachusetts College of Education Annual Research Showcase, Amherst, MA.

Piantaggini, L., (2024, September 19). False Formatives: Student Perception vs. Teacher Practice of Classroom Assessment & Grading [Poster session], NCME Special Conference on Classroom

Assessment, Chicago, IL.

Reedy, R. (1995). Formative an summative assessment: A possible alternative to the grading-reporting dilemma. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 79(573), 47.

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117714

Shepard, L. A., Penuel, W. R., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2018). Using Learning and Motivation Theories to Coherently Link Formative Assessment, Grading Practices, and Large‐Scale Assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 37(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12189

Shepard, L. A. (2019). Classroom Assessment to Support Teaching and Learning. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 683(1), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716219843818

Siegel, M. A., & Wissehr, C. (2011). Preparing for the Plunge: Preservice Teachers’ Assessment Literacy. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 22(4), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-011-9231-6

Stiggins, R. (1994). Student-centered classroom assessment. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED420667

Townsley, M. (2022). Using Grading to Support Student Learning (1st edition). Routledge.

Tyack, D. B., & Cuban, L. (1997). Tinkering toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform (Revised edition). Harvard University Press.

White, B. Y., & Frederiksen, J. R. (1998). Inquiry, Modeling, and Metacognition: Making Science Accessible to All Students. Cognition and Instruction, 16(1), 3–118. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1601_2